While American investors were busy enjoying their Thanksgiving dinners, global markets were shaken by word that Dubai asked for a payment holiday on the $59 billion it owes via its investment vehicle, Dubai World. The move, which comes as oversized bets on Persian Gulf real estate sour, was considered a default by the major rating agencies.

Last week's "standstill" request puts at risk up to $80 billion in debt linked to the emirate. While this is small in the context of the $3 trillion in losses written down by global banks since the credit crisis began, it may very well result in the largest country debt default since Argentina in 2002.

So while Dubai is insignificant on its own, and will likely be bailed out by its larger and much wealthier neighbor and fellow United Arab Emirates member, Abu Dhabi, it ignited much larger concerns over the fiscal health of governments around the world. I discussed these concerns early last week in an in-depth discussion over rising insurance costs on government bonds.

This highlights concerns over the ability of governments to service their rapidly rising debt loads. Those on the hot seat include Greece, Japan, and much of emerging Europe. I wrote about these concerns last week when we discussed the recent rise in the cost to insure against default on public debt.

So, is this the beginning of a new crisis? The team at Capital Economics in London doesn't believe it is: "Dubai's current problems are a long overdue consequence of the bursting of the global property bubble rather than the start of a new financial crisis. Nonetheless, they are a timely reminder that the legacy of past excesses in heavily-indebted economies will linger for many years to come."

In other words, imagine that the global financial system is like a patient recovering from a near fatal case of pneumonia. After being pumped with fluids and antibiotics via stimulus spending and ultra-low interest rates, the patient is on his feet again. But that doesn't mean he isn't vulnerable to a persistent cough and a low-grade fever.

Plus, Dubai was the country-sized equivalent of a full-tilt Miami condo flipper. The United Arab Emirates pegs its currency to the U.S. dollar, which means that it imported interest rates that were too low for its fast growing economy -- resulting in a credit bubble and asset boom. Property prices have since fallen by 50% over the last 12 months. What's worse is that efforts to diversify its economy away from fossil fuels via free-trade zones made the country extremely vulnerable to a slowdown in global trade and a decline in financial markets.

It was an extreme case of the kind of overleveraged excesses that resulted in the 2007-2008 financial crisis in the first place. The country's investment arm spent billions on artificial islands reclaimed from the Persian Gulf in the shape of palms. It took a stake in a new $8.5 billion MGM Mirage (NYSE: MGM) hotel in Las Vegas. It invested in Canadian performance troop Cirque du Soleil. It bought stakes in Aspen ski resorts. It bought the Queen Elizabeth II ocean liner.

In other words, imagine that the global financial system is like a patient recovering from a near fatal case of pneumonia. After being pumped with fluids and antibiotics via stimulus spending and ultra-low interest rates, the patient is on his feet again. But that doesn't mean he isn't vulnerable to a persistent cough and a low-grade fever.

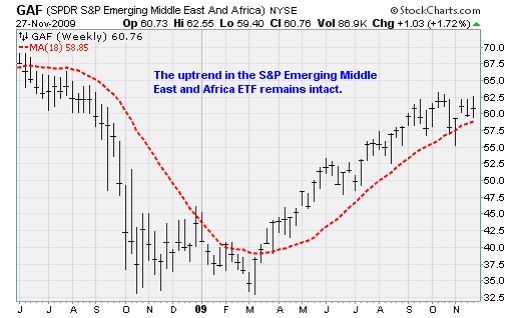

While the impressive rally over the past few months have brought a period of relative calm, it has merely masked the vulnerabilities that still remain. Investors were lulled into a sense of false security and Dubai's rulers rudely awakened them. But apart from the jarring psychological effect, the risk that Dubai's debt restructuring will result in a global "contagion" that pulls down financial markets and undermines the nascent economic recovery remains low.

Market Action

As traders returned from their holiday, they wasted no time in responding to weakness in Asia and Europe as a wave of fear spread: The Dow Jones Industrial Average lost 1.5%, the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index, the Nasdaq Composite Index lost 1.7%, the Russell 2000 lost 2.5%.

Stocks and commodities weakened, risky credit sold off, and the dollar and U.S. Treasury debt rose as investors sought safe havens. The CBOE Volatility Index or "Fear Index" was up 26.5% at one point -- a jump of a magnitude that hasn't been seen since the Lehman Bros. collapse. According to Tim Backshall at Credit Derivatives Research, credit markets had their worst day since March 5.

Intra-day losses were severe: The Dow was down 2.2% at one point. But an afternoon rally cut the losses. And over in Europe, where banks are expected to have a combined Dubai bond exposure of $40 billion according to Credit Suisse Group AG (NYSE ADR: CS) estimates, stocks climbed on Friday after deep losses on Thursday. This could be a sign that as investors learn the true nature of the Dubai situation and realize it isn't the beginning of a new credit crisis.

For the week, the Dow lost 0.1%, the S&P 500 lost 0.4%, the Nasdaq lost 0.4%, and the Russell 2000 lost 1.3%. It was the Dow's first weekly decline since mid-October.

Technically, the S&P 500 has struggled to overcome resistance at the 50% retracement line measured from the Oct. 07 high to the Mar. 09 low. A breakout would see a move to 1,200 for a gain of 10% where new resistance would be met. While this would be nice, my research suggests the market has lost so much momentum that such a move isn't likely without a pause to recharge the batteries.

A breakdown here would likely see a move to the 1,000 level, for a possible decline of as much as 8% in a retest of the September low. Such a move would feel catastrophic but would be well within the bounds of a normal 10% correction in the context of a long-term bull market. This would shake off speculative excess and set the stage for a decisive move over the 1,200 level on the SPX.

Yellow Fever

Given the ferocity of gold's advance and the pressure being exerted on the dollar, the yellow metal's rise could last longer than most expect. But the movement is unsustainable just as the Nasdaq's rise between 1998 and 2000 was unsustainable; just as home price appreciation in 2006 was unsustainable; or how the frenzy surrounding Dutch tulip bulbs in the 1600s was unsustainable.

The dramatic movements in gold and the dollar are being driven by a psychologically potent mix of fear and greed. Normally, these two emotions are mutually exclusive with one occurring during boom times and the other accompanying periods of panic. But now, both are encouraging people to sell the dollar and buy gold: Fear over the loss of the dollar's purchasing power and greed as gold climbs makes it climb towards the heavens.

Remember that gold has no intrinsic value. It has no cash flows. It serves no practical purpose. It costs money to store and protect. And its value has fluctuated greatly throughout human history: Between 1980 and 1999, gold lost 71% of its value.

As for the dollar, let's be clear: It will not collapse. And it is a long way from losing its status as the world's main currency. This fear is increasingly widespread, but it isn't realistic. It would result in dramatically higher interest rates and more expensive oil and other imported goods for American consumers. In addition, the U.S. government would be forced to cut spending and hike taxes as financing the deficit became more difficult. The result would be a hellish recession that makes our current affair seem like child's play.

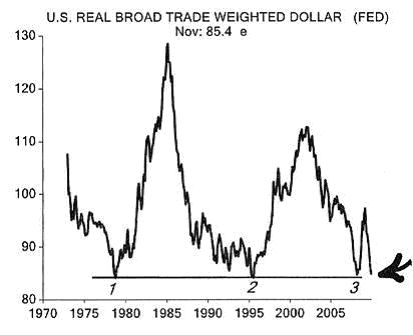

Exporters in Asia and the Persian Gulf understand this and aren't keen on pushing the global economy off the cliff. Indeed, Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh recently said that there is no substitute for the dollar as the global reserve currency. And the economists at the ISI Group note that the real trade-weighted dollar index -- which corrects for inflation and reflects the relative important of America's trade partners -- has fallen to a historical low that has held three times over the last thirty years.

So, it increasingly appears that central banks are using the IMF's gold sale (being done to raise money to pay its bills) as a rare diversification opportunity. But it's not a reflection of wholesale abandonment of the dollar no matter how badly the gold fanatics want to believe it.

Another possible explanation is the huge inflation many are awaiting given the massive money supply expansion over the last year. According to John Williams of Shadow Government Statistics, who reconstructs the discontinued broad M3 measure of money, the monetary base is up 129% since last August. My contacts in the hedge fund industry say that governments, central banks, and investors are pricing in inflation expectations five years out.

But this too is highly speculative: Industrial activity remains well below capacity and wage pressures should continue as the unemployment rate remains buoyant. The anecdotal evidence is also mixed. A rise in inflation-adjusted Treasury debt isn't being matched by decreases in non-adjusted Treasury bonds.

I've been recommending that my subscribers play along for now, cynically following the herd and profiting from gold's advance via our position in the StreetTracks Gold Trust (NYSE: GLD). But we will refuse to drink the Kool-Aid and will remain vigilant as we watch for signs of a reversal given that rapid, parabolic advances tend to be followed by similarly rapid, parabolic declines.

Technical analysis provides a few clues on timing. While gold has reached overbought territory on its 14-week RSI, recent history suggests multiple incursions over the 70 threshold are needed to fully exhaust bullish sentiment. So while a near-term pullback is likely, it probably won't mark the end of the secular advance. Also, this analysis suggests gold's bull run has another six months or so to go before pulling back for good.

Week in review

Monday: A number of comments by Federal Reserve officials encouraged traders to sell the dollar short and push stocks higher. First, St. Louis Fed president James Bullard said that he would like to keep the Fed's direct purchase authorization for mortgage-backed securities alive past the March deadline. If implemented, Bullard's wishes would help ensure that mortgage rates remain low and would give the housing market further times to heal.

Separately, Chicago Fed President Charles Evans said that interest rates may stay near 0% until "late 2010, perhaps later" as policymakers await improvement in the job market.

These comments I've expressed many times in the past six months: Inflation hawks can complain all they want about U.S. money being too cheap, but the Fed is likely to keep short-term interest rates low until it has seen at least four to six months of employment growth in the United States. That won't happen until late in the second half next year, at the earliest.

Tuesday: The government's estimate of third-quarter economic growth was revised down to 2.8% from the original 3.5% mainly on less consumer spending, fewer exports, and a reduction in business inventories. Still, Q3 marks the first economic expansion since the slight rise in the middle of 2008.

On the housing front, the latest numbers from the Case-Shiller home price index covering 20 metropolitan areas squeaked out a 0.3% gain in September -- suggesting some of the wind is being taken out of the nascent housing recovery. Back in August, the index gained 1.2%. Overall, the index is up 3.5% from the low set in May as prices have returned to levels that prevailed in the autumn of 2003.

Wednesday: A heavy economic calendar. The latest weekly jobless claims number was the day's big economic report: The measure of job loss finally fell below the 500,000 threshold for the first since October 2008. While the loss of half a million jobs a week is still terrible, history suggests a sub-500k number increases the probability of a positive monthly payroll report and a reduction in the unemployment rate.

Historically, jobless claims in excess of 500k are associated with payroll losses of 245,000. Jobless claims between 450k and 500k are associated with losses of 40,000. And finally, claims between 400k and 450k are associated with a payroll expansion of 65,000. This means we will probably see a positive payroll report within the next two months or so -- providing a huge confidence boost to consumers and investors alike.

In other news, consumer spending increased 0.7% in October, beating expectations and reversing the 0.6% decline in September thanks to a 0.2% expansion in incomes. Consumer sentiment was higher than expected but still below levels reached this summer. The one blemish: Durable goods orders fell 0.6% in October, coming in below the 0.5% expansion analysts predicted and the 1% expansion in September.

Thursday: U.S. markets closed for Thanksgiving holiday. Stocks in Asia and Europe fell on Dubai debt concerns.

Friday: Black Friday kicked off the holiday shopping season. Retailers reported strong crowds. Marshal Cohen at market research firm NPD Group said the day was driven by a mix of "pent-up demand and frugal fatigue." Let's hope it lasts.

The Week Ahead

Monday: The Chicago Business Barometer will provide an update on manufacturing activity in the Midwest.

Tuesday: Motor vehicle sales, the Institute for Supply Management Manufacturing index, and construction spending will all be reported. Vehicle sales will be closely watched as investors gauge true consumer demand now that the affects of the government's cash-for-clunkers scheme have dissipated.

Wednesday: The ADP Employment report will provide a preview of the big employment situation report on Friday.

Thursday: Chain-store sales will tell us just how effective all those Black Friday promotions were in encouraging holiday shopping. Also, the weekly jobless claims report.

Friday: The employment situation report is expected to show a payroll decline of 100,000 and the unemployment rate unchanged at 10.2%.

[Editor's Note: For the first time in 70 years, U.S. T-bills are paying 0% interest, while U.S stocks are continuing to rise. According to Bloomberg News, this last happened in 1938, when T-bill yields fell from 0.45% to 0.05%. Then came 1939, when stocks began a three-year slide that took the S&P down 34% after the U.S. Federal Reserve prematurely boosted borrowing costs to battle phantom inflation.

Sounds eerily like the present, doesn't it?

Very few market columnists see the parallels. And even fewer see the differences. But as this column demonstrates, veteran portfolio manager, commentator and author Jon Markman sees it all. And that's why investors subscribe to his Strategic Advantage newsletter every week.

To navigate today's markets, investors need a guide. Markman is the ideal choice.

For more information, please click here.]

News and Related Story Links:

- The Wall Street Journal:

Dubai Jitters Infect Debt of Sovereign Spendthrifts. - Capital Economics:

- Official Web Site.

- Cirque du Soleil:

The Week Ahead.