During the height of the Deepwater Horizon tragedy four years ago, I had my graduate students monitor the flow of oil from the sunken platform in the Gulf of Mexico.

Most of their work involved rather straightforward calculations based on undersea camera footage.

But from time to time, flimsy protoplasmic-like structures would float across the screen. The students called them "ghosts."

One student even casually wondered, "What if the ghosts had caused all of this?"

With that, I walked over, checked some figures, and immediately called the U.S. Coast Guard contingent that was overseeing the data from the disaster.

Fast forward to today, and there have been some equally disquieting discoveries in the news of late.

So what do mysterious holes in the Siberian permafrost, hundreds of gas plumes off the East Coast of the United States, and our "ghosts" apparently have in common?

It seems to be icy methane hydrates, touted by some as the fuel of the future...

Siberian Craters & the "Ghosts" of Deepwater Horizon

According to an April study issued in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, permafrost soil, which typically remains frozen all year, is thawing and decomposing at an accelerating rate.

This process is releasing more methane into the atmosphere, causing the greenhouse effect to increase global temperatures, potentially creating a positive feedback situation in which even more permafrost begins to melt.

"The world is getting warmer, and the additional release of gas would only add to our problems," said Jeff Chanton of Florida State University, a member of the study group. He added that, if the permafrost completely melts, there would be five times the current amount of carbon equivalent in the atmosphere.

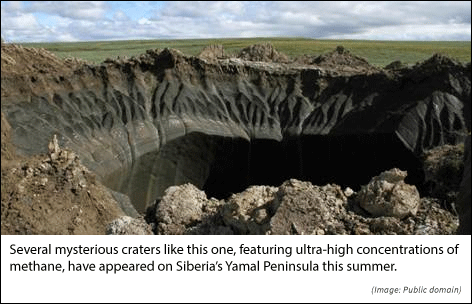

Unfortunately, that corresponds with what Russian scientists found when they analyzed the giant mystery craters that were recently discovered in the Siberian Yamal Peninsula.

Andrei Plekhanov of the Russian Scientific Center of Arctic Studies, who led an expedition to the first crater, told the journal Nature in late July that his team found concentrations of methane approaching 9.6% at the crater's floor.

That's more than 53,600 times higher than the average of amount of methane usually found in the atmosphere (measuring 0.000179%).

That's more than 53,600 times higher than the average of amount of methane usually found in the atmosphere (measuring 0.000179%).

Now scientists are worried that warming temperatures are going to create the conditions for more permafrost melting, releasing additional methane in those areas (like Yamal) where there are major natural gas deposits.

Then there is the problem that was recently disclosed.

On Sunday, August 24, a study released online in the publication Nature Geoscience described the discovery of 570 plumes of methane "percolating" off the East Coast of the United States.

The research is based on data collected in a survey from 2011 to 2013 by the research vessel Okeanos Explorer. Equipped with multi-beam sonar along its hull, the vessel not only mapped the sea floor along a path off the coast of North Carolina to Massachusetts, but also recorded the reflections in the water column, discovering the distinctive signature of methane gas bubbles.

Most of the seeps were found at depths of 180 to 600 meters along the upper slope of the continental margin. This is the area where the continental shelf rapidly falls off to a 5,000 meter deep ocean plain.

As Science reporter Eric Hand puts it: "The seeps suggest that methane's contribution to climate change has been underestimated in some models. And because most of the seeps lie at depths where small changes in temperature could be releasing the methane, it is possible that climate change itself could be playing a role in turning some of them on."

The Energy Trapped in Ice Is Enormous

Apart from the relationship between climate change concerns and methane emissions, there is another factor to consider when it comes to methane hydrates.

And it's one that puts this entire discussion of alien-looking holes in the Siberian wilderness and columns of bubbles in the Atlantic squarely in our area of interest. Methane hydrates are seen by some as the next major source of energy.

In fact, Japan - a nation dependent upon imports for virtually all of its energy - has embarked on the largest project ever attempted to develop vast reserves of offshore methane hydrates.

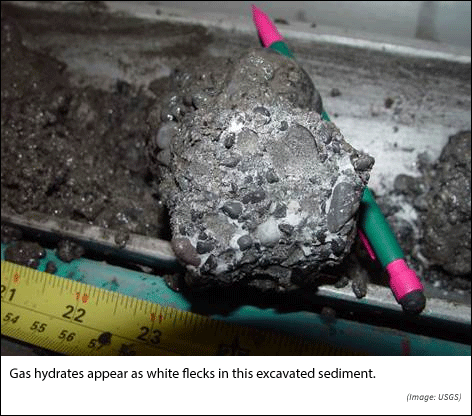

Methane hydrate, or methane clathrate, is an ice-like substance that consists of methane gas and water. Methane is the chief ingredient in natural gas. Since this substance is highly flammable, it's sometimes referred to as "fire ice."

The Arctic region in general and the area off Alaska in particular, are known to have expansive amounts of these hydrates.

So how much energy are we talking about?

The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that gas hydrates could contain between 10,000 trillion cubic feet to more than 100,000 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. When brought to the surface, one cubic foot of gas hydrate releases 164 cubic feet of natural gas.

The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that gas hydrates could contain between 10,000 trillion cubic feet to more than 100,000 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. When brought to the surface, one cubic foot of gas hydrate releases 164 cubic feet of natural gas.

However, as Hand points out, "This immense reservoir is thought to contain 10 times as much carbon as the atmosphere."

That is where any attempt to develop this plentiful new energy supply encounters a major potential roadblock.

Hand puts it this way...

"The gas, if it reaches the atmosphere, is far more potent than carbon dioxide as a heat trapper. Even in the more likely event that aerobic microbes devour the methane while still in the ocean, it is converted to carbon dioxide, which leads to ocean acidification. Some scientists have implicated runaway methane hydrate releases in the catastrophic extinctions of marine life at the Permian-Triassic boundary, 252 million years ago."

Think of the danger this way, you could have a major aquatic biosphere one year and nothing the next.

So while natural gas is often touted (quite correctly) as a cleaner source of energy than either crude oil or coal, methane hydrates could become a huge greenhouse gas problem.

Now, I admit that it will be difficult to establish climate change as the cause of the emissions in Siberia and the Atlantic.

But the broader concerns over what the "dirtier" (i.e., much heavier carbon concentrated) methane hydrates could do environmentally are another matter entirely. The emissions now capturing the attention of the press could well trigger additional climate problems in a dangerous cycle of cause and effect.

And there is another disquieting revelation. Methane hydrates can become unstable... and explode. That seems to be what happened in Siberia.

That brings me back to my student's observation in 2010. Because the "ghosts" he was watching were dissolving hydrate chains floating up from the seabed in the immediate region surrounding the wellhead.

I still think this was the primary cause of the Deepwater Horizon tragedy.

About the Author

Dr. Kent Moors is an internationally recognized expert in oil and natural gas policy, risk assessment, and emerging market economic development. He serves as an advisor to many U.S. governors and foreign governments. Kent details his latest global travels in his free Oil & Energy Investor e-letter. He makes specific investment recommendations in his newsletter, the Energy Advantage. For more active investors, he issues shorter-term trades in his Energy Inner Circle.