European financial authorities have high hopes for quantitative easing across the Eurozone, but few know exactly how European Central Bank QE works.

ECB QE is a very different animal than similarly named methods in the United States and Japan. European Union treaties and German outcry over inflationary "money printing" measures have forced the ECB to pursue a program with a number of limitations.

When ECB president Mario Draghi announced ECB QE in a January 2015 ECB meeting it sounded rather simple.

ECB QE would be a 60 billion euro ($66.2 billion) a month bond-buying program. It would last from March 2015 to at least September 2016, aimed at bringing inflation up to a target rate of 2%. This would, over 19 months, add 1.1 trillion euros ($1.2 trillion) to the Eurozone financial system.

Those numbers are worth a closer look, but first, here's how QE works...

How ECB QE Works - Part 1: The Basics of QE

It's important to understand that ECB QE is not "money printing." And even just by itself, it's not inflationary.

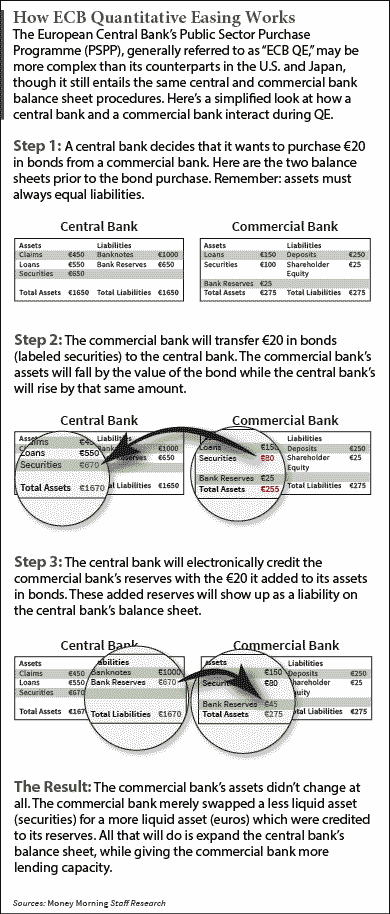

Here's how it works. The European Central Bank - or one of the Eurozone member's national central banks - will transfer a government bond from a commercial bank's balance sheet to its own. The bond will show up on the asset side of the central bank's balance sheet. Then the central bank will credit the commercial bank's reserve account the value of that bond.

The central bank's balance sheet will increase on the asset side by the value of the bond, and the liabilities by the increase in value of the commercial bank's reserve account.

But in this transaction, the commercial bank's balance sheet doesn't change at all in value, only in composition. It is an asset swap. The commercial bank swaps a less liquid asset (a government bond) for a more liquid asset (euros).

All this does is increase liquidity within the commercial bank. It allows the banks a larger capacity to issue more loans.

As firms and households borrow that money and credit expands, more money is moving around in the economy. This is known as the velocity of money. It's this velocity that's supposed to help fight deflation and get dollars moving in the private economy.

In short, QE is an effort to facilitate a higher velocity of money by giving banks more lending capacity.

Now, here's how European Central Bank QE works...

How European Central Bank QE Works - Part 2: Avoiding "Fiscal Transfers"

In authoring a Eurozone QE program, the ECB had its hands tied.

EU treaties call for a separation of fiscal and monetary policy authority. Fiscal policy is the responsibility of its members. Monetary policy is the responsibility of the ECB.

This explicit distinction has been a headache for some of the weaker Eurozone members like Greece, which can't employ monetary policy to finance debts once they spiraled out of control.

You see, there is not one so-called "Eurobond." Each member issues its own debt and it is the sole responsibility of that country to pay it back.

Were there a single bond, any country could issue debt in the name of the whole Eurozone. So if Greece issued debt through a Eurobond and defaulted, it would fall on the stronger economies to help make up the losses. This would constitute a "fiscal transfer," and Germany - and other Eurozone members - would effectively have a hand in Greek fiscal policy, which violates EU bylaws.

So Europe was left with this 1.1 trillion euro ($1.2 trillion) program.

It's worth peeling these numbers back a bit. Of that 60 billion figure, 10 billion euros ($11 billion) were simply a continuation of an asset purchasing program that was already happening. In fall 2014, the ECB announced a smaller-scale program to purchase a combination of covered bonds and asset-backed securities. That will comprise 190 billion euros ($209.5 billion) of the 1.1 trillion euro program.

The remaining 50 billion euros ($55.1 billion) would be the sovereign debt of Eurozone members. This will account for 950 billion euros ($1.1 trillion) of Eurozone QE.

Now, here's where it gets a little complicated...

How European Central Bank QE Works - Part 3: A Closer Look at QE's 50 Billion Euros a Month

The ECB took careful note of any measures that would constitute a fiscal transfer. And while they didn't avoid the issue altogether, they did work to minimize it.

As mentioned earlier, there's no single bond that the ECB can purchase. So QE has to be spread out across purchases of 19 members' bonds. And what's more, the ECB had to make sure to make bond purchases in proportion to a country's ability to take on debt.

You see, if the ECB did heavily favor, say, Spanish debt over German debt in its purchases, Spain would have a better chance of defaulting when paying interest on central bank purchases, and then the stronger economies would have to foot the bill for the losses. It would essentially be the same as issuing a Eurobond.

That's why bond purchases would be spread out across Eurozone countries based on the so-called "capital key." The capital key is the amount of paid-up capital the National Central Banks (NCBs) pay to build up the ECBs equity, and it is in proportion to that country's share of the Eurozone's population and GDP.

So, for example, the largest economy, Germany, would make up 25.6% of the government bond purchases. But Malta would only make up 0.1% of those purchases.

But then again, why would the ECB target more German bond purchases when a country like Spain needs more monetary policy relief? These were the questions that lead the ECB to include some risk-sharing in its QE program.

The ECB approach would make 80% of euro purchases not subject to risk-sharing. This means 40 billion euros ($44.1 billion) would be NCBs purchasing their own countries debt (e.g. the German Bundesbank buying German debt).

The other 20% of bond purchases are subject to risk-sharing. Any losses on up to 10 billion euros of the program due to member defaults would have to be covered by all Eurozone countries - not just the country defaulting.

The 20% shared risk can be broken down even further. Of the QE program, 12%, or 6 billion euros ($6.6 billion), will be purchases of debt from supranational institutions. These are bonds issued by institutions built up by shared Eurozone capital, such as the European Financial Stability Fund, the European Investment Bank, and the European Stability Mechanism. The purchases will also be made by NCBs in proportion to the capital key.

The other pool of bonds subject to risk-sharing is the 8%, or 4 billion euros ($4.4 billion) a month, of purchases that the ECB will make directly from Eurozone members.

So here's how the final monthly tally of those 60 billion euros a month breaks down:

- 10 billion euros will be asset purchases made under existing asset-purchasing programs.

- 40 billion euros will be NCB purchases of its member country's treasury debt, in proportion to its capital key.

- 6 billion euros will be purchases of supranational institutions debt, such as the EFSF, ESM, and EIB, by NCBs, also in proportion to its capital key. This is subject to risk-sharing.

- 4 billion euros will be purchases made directly by the ECB of member debt in proportion to capital key. This is also subject to risk-sharing.

How European Central Bank QE Works - Part 4: Further Eurozone QE Limitations

There is one more piece needed to put together the puzzle of how ECB QE works from here...

The ECB has taken even further painstaking measures to disavow itself of any fiscal policy responsibility.

[epom key="ddec3ef33420ef7c9964a4695c349764" redirect="" sourceid="" imported="false"]

The first of which is to limit QE purchases to buying debt in the secondary markets. That means all purchases will come from the commercial banks. The ECB does not want to be buying at auction and influencing bond prices at the level that market-making banks do at treasury auctions in the primary markets.

Additionally, of any bonds that either the ECB or NCBs buy, they have to keep purchases below 25% of any one bond issuance. Bonds of the same maturity and yield are sold in the primary markets in blocks, of any one block; the ECB doesn't want to hold what's called a "blocking minority."

If the ECB holds a "blocking minority" on any issuance, it's afforded the right to block a restructuring of debt in the case of a default. The ECB does not want to even be in a position where it holds that power, lest it be accused of overstepping into fiscal policy.

And the final piece of bond-buying limitations prohibits the ECB from holding 33% of a member country's debt. This is another measure to ensure the market for these bonds can achieve proper price discovery without too much influence from central bank purchases.

These limitations to Eurozone QE are important because they may ultimately put a straitjacket on the program.

For example, through an earlier bond-buying program, the Securities Market Programme (SMP), the ECB already holds debts on its books of Eurozone governments. This will limit its purchases of debt from Italy, Ireland, and Portugal before it does hit that 33% figure. And the ECB will not be able to buy any Greek debt, as it already holds 33%, until some its holdings mature in August.

Given all these limitations, the Bruegel Policy Contribution estimates that in the 19-month timeframe, ECB QE will only be able to buy 799.7 billion euros ($881.7 billion) in government bonds, far short of the 950 billion euros expected under the monthly purchasing program.

Is Eurozone QE really fixing what ails Europe? After all, Greece is the biggest question among the 19-member currency bloc. It's Greece's potential exit - or debt default. A "Grexit" means the Eurozone is too fragile to keep itself altogether. But a default would mean the Eurozone allows its members to run up debts with impunity. Just how big is the pile of Greek debt that we're talking about? We break that down here...