Ahh, the options listing... Trust me, it isn't as bad as it looks.

It starts with understanding a rather long set of symbols that looks something like this:

GOOG120317P600000

This code is simply the ticker symbol for your option. And once you break it down, you'll find that it holds a wealth of information, including all the "standardized" terms we talked about in this article.

The first three or four letters are just the stock ticker for the specific underlying stock, in this case, Google Inc. (NasdaqGS: GOOG):

GOOG120317P600000

The next two digits tell you the year the option expires. This is necessary because long-term options last as far out as 30 months, so you may need to know what year is in play. In this case, the Google option is a 2012 contract:

GOOG120317P600000

The next four digits reveal the month and the standard expiration date. The expiration date does not vary. It's always the third Saturday of the month. And the last trading day is always the last trading day before that Saturday, usually the third Friday (unless you run up against a holiday). In this case, you've got a March contract (03). And the third Saturday of March 2012 is the 17th.

GOOG120317P600000

Now you'll see either a C or a P, to tell you what kind of option you're dealing with - a call or a put. This one happens to be a put:

GOOG120317P600000

After that comes the fixed strike price, which is 600:

GOOG120317P600000

Finally, any fractional portion of the strike is shown at the end. This comes up only as the result of a stock split, where a previous strike is broken down to become a strike not divisible by 100:

GOOG120317P600000

Now that you're a pro, let's take it a step further.

Reading the Options Table

The numbers part doesn't have to be painful or tedious.

In fact, when "real money" (translation: your hard-earned cash) is at stake, I think you'll find this data is suddenly much more interesting.

An options listing gives you the status of the four standardized terms you already know: Type of option, expiration, strike, and the underlying security.

The listing is set up for all of these criteria, and then also provides the two current prices for each strike - the bid and the ask.

Why two prices? Well, the bid is the price at which you can sell an option, and the ask is what you'll pay to buy it. And the difference between the prices - the bid-ask spread - is the profit for the "market maker" who places the trades.

Now let's look at a typical options listing.

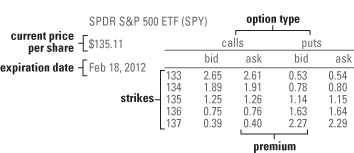

This one is for options on the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (NYSE: SPY), with two different expiration dates and five different strike prices. After those dates, all of the options will expire worthless, so you have to take action (closing a position, exercising, or for short sellers, being exercised) by the last trading day of the period (the Friday right before the listed dates).

After that, the options contract is over, and the "option" to act simply ceases to exist.

The strikes range from 133 to 137 for both expiration cycles.

By the way, this ETF is an example of a very flexible option trading venue, because strikes are found in one-point increments. In comparison, stocks selling in this price range usually provide strikes in 10-point increments, so you would only be able to choose from strikes of 130, 140 or 150. That gives you much less flexibility for any combination strategies (spreads or straddles).

Okay, so as you can see, the four columns are broken down into two main parts. The first two are the bid and ask prices for calls, and the second two are bid and ask for puts.

Notice how the prices move. For calls, the lower the strike, the higher the premium. This is because, remember, a call is a bet that the price will go up. A lower strike, closer to the current price, is more probable, so you have to pay more for it (or you get more, if you're selling). Below the current price of the ETF ($135.11 per share as I write this), the calls are "in the money" (ITM); and above, they are "out of the money" (OTM). The further in the money, the richer the option premium.

You see the opposite price movement in the puts.

The higher the strike, the larger the premium - and for the same reason. Remember, puts are ITM when the strike is higher than the current price per share. The more in the money, the higher the premium.

The later expirations are all more valuable than the earlier ones, even though the strikes are the same. That's thanks to - you guessed it - time value. One additional month is in play. There's more time value left, and more likelihood of some crazy price swing, so the premium is higher.

There's a trade-off, of course.

Later expirations means you have to leave those positions open longer. So the desirability of a higher premium depends on whether you take up a long position or a short one.

Long positions are more expensive when you have more time to expiration. At the same time, this provides more chance for the underlying to move in the desired direction. So picking a long position is a balancing act between time and cost.

Short positions, on the other hand, benefit from time decay.

When you sell an option, you receive the premium and wait out the time decay. Depending on whether the option is ITM or OTM, you can let it expire, close it out with a "buy to close" order, or roll it forward. (More on that soon.)

And that's all! See, I told you it wasn't that complicated.

Related Articles and News:

- Money Morning:

Options Trading: The Most Important Piece of Advice for Beginners - Money Morning:

Options Trading Strategies: Slash Your Risk and Make Money - Money Morning:

Options Trading Strategies: Taking the Mystery Out of Puts and Calls - Money Morning:

How to Trade Gold with ETFs and Options - Money Morning:

How to Trade Weekly Options