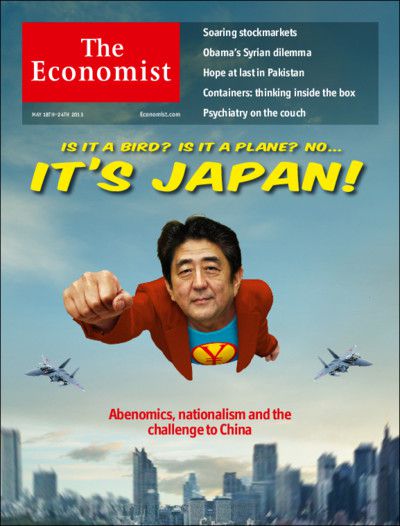

A few weeks ago The Economist depicted Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe as a super-hero on its May 17 cover. Noting specifically, "Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No....It's Japan."

Knowing what I know about how magazine covers tend to affect the markets, I could only shake my head.

Not only do I think the cover is the harbinger of "Abe-doom," but The Economist may as well have handed him a ginormous lump of kryptonite.

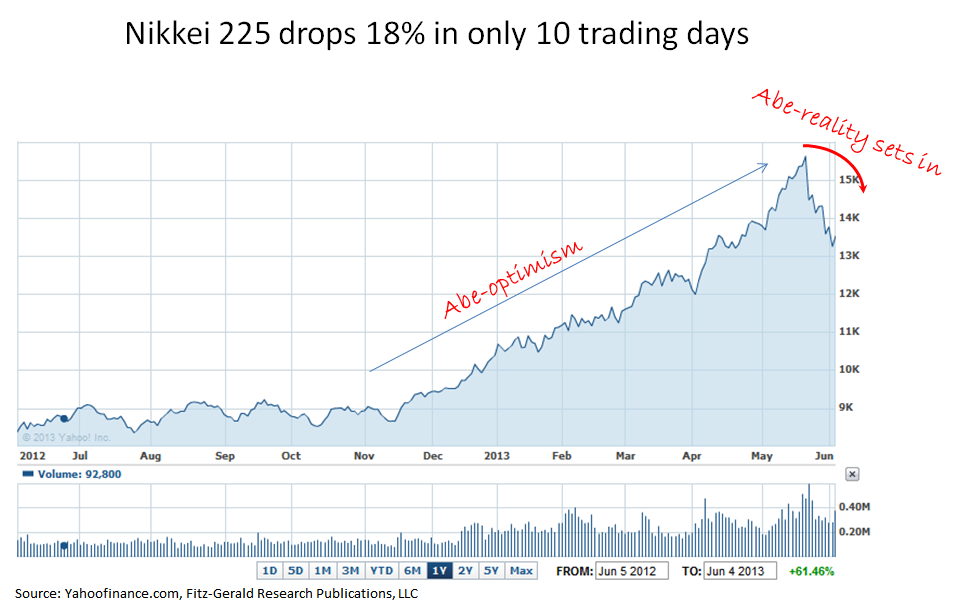

After rising 80% from last year's lows, Japanese stock prices have done a U-turn and unceremoniously have begun to return to earth, falling more than 18% in 10 consecutive trading sessions as of last Wednesday.

The Nikkei regained some ground in wild trading that saw it up 4.94% on Monday and it's still up 56.7% over the past 12 months, but don't hold your breath. "Super Abe" has pulled out every stop, and the markets won't think it's enough for much longer.

What's interesting about that is this actually isn't Abe-san's fault. No, the markets completely ignored history and built in such outrageous expectations that anything short of an economic miracle will be disappointing.

Today I want to address the two questions on everybody's mind: Is such volatile trading the start of a major reversal? Or is it a precursor to still-higher trading ahead?

And, what can you do about it?

The Flip-side of Reverse

Let's start with the notion of a reversal.

Parabolic charts are never good, no matter what asset class, stock or individual security you're considering. They are not the signs of growth that many think they are. Instead, parabolic charts like the Nikkei's over the past 12 months have historically suggested imminent collapse.

The reason is simply that exponential growth cannot continue indefinitely because it's unsustainable. In scientific terms, it's impossible to maintain the conditions needed for systemic survival.

In practical economic terms, the situation is no different. However, it's not just the conditions that matter. You have to consider market psychology, too.

The markets got way ahead of themselves based on nothing more than the collective hopes for Abenomics. Now, unfortunately, they're going to have to come to terms with the results...or in this case, lack thereof.

It's not that the thinking is bad. It's wrong given what we know about long-term monetary history, but not necessarily bad. As a market professional, I'm happy to capitalize on whatever is driving the markets.

So what's hit the fan?

When Prime Minister Abe introduced his plans to inject three times the amount of comparative stimulus Bernanke had into his country's economic machine despite the fact that it is one-third the size of the U.S. markets, it was viewed as a good thing because it would weaken the Yen.

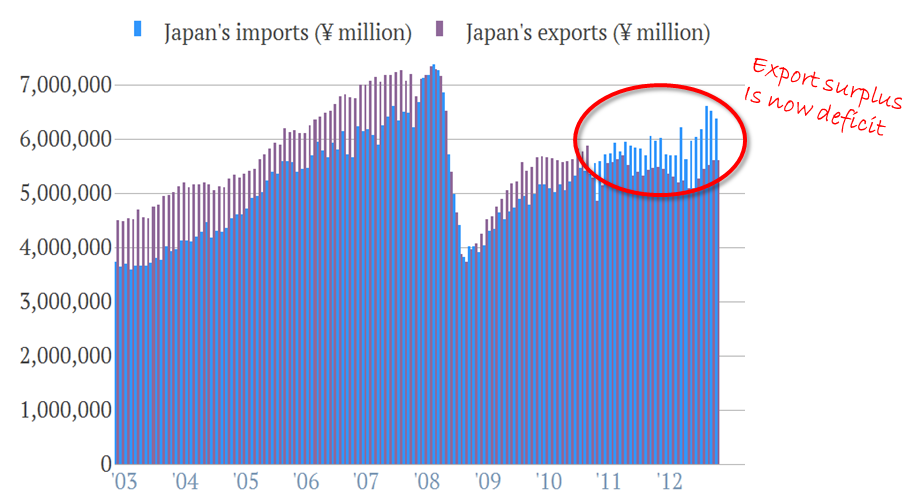

After all, went the thinking, Japan is an export nation, so the weaker Yen would make Japanese products more competitive in global markets. The Nikkei took off.

What those folks missed was the fact that Japan has no raw materials of its own to speak of. Therefore, in order to build up exports, Japan's industrial giants would have to build up raw material imports...sharply.

And that's exactly what's happened.

Imports are up sharply and threatening to overwhelm any competitive advantage from lower-priced exports because the costs of manufacturing jumped significantly. This is particularly true for energy-related expenditures, which are now running at post-quake highs. Very shortly, this is going to work its way into quarterly reporting and the numbers won't be good.

Especially when you consider that former export surpluses are now deficits.

Source: Quartz, FactSet, Fitz-Gerald Research Publications, LLC

This exposes another dangerous flaw in Abe's programs.

Deflation-busters

Investors and politicians alike have assumed that Prime Minister Abe and his sidekick, Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda, want higher inflation because that's what they've heard about his unlimited stimulus programs...that they're supposed to more than double it to 2%.

In reality, Abenomics are supposed to end deflation.

I'm not splitting hairs. Stopping deflation is very different from creating inflation, especially when you're talking about the imports I've just mentioned. Over 50% of what Japan imports is initially priced in dollars.

So while Japanese exporters are enjoying a boost from the falling Yen, those who are selling into the island nation are loving the boost that's coming from dollar-based goods, especially when they can raise prices at the same time to compensate for tighter conditions.

Over time, what this suggests is that the short-term boost in exports Japan's enjoying today will be cannibalized by the rising cost of imports when prices adjust, effectively negating Abenomics' gains.

So now what?

Japan's got an identity crisis.

Take Japanese bonds, for example. Abe's policies should create inflation that's a bond killer. Yet, a fundamental element in the Bank of Japan's policies at the moment is the continued monetization of Japanese debt which, in plain English, means buying bonds...lots of bonds.

The result is unprecedented volatility in Japanese government bonds and not one, but three global stock market swoons in the last eight weeks caused by Japanese Value at Risk models coming unglued because of it. Nobody knows if they should be buying or selling...except us.

And I'll get to that in a minute, but I have to explain something first.

Many investors have fallen for the very seductive siren of stimulus. While not exactly believing that things will get better, they have placed their faith in an economic doctrine for which there is no precedent of success. Short term, perhaps...but longer term, no - but that's a story for another time and one we've covered extensively in Money Morning.

What's vitally important to understand right now is that Japan has any number of structural challenges that are well beyond whatever Prime Minister Abe cooks up.

For example, the country's energy markets remain completely dependent on global pricing and largess. With no practical homegrown alternatives, Japan has to import at least 80% of its energy.

Most of the country's economic system is hopelessly over-regulated. This robs private capital of return and incentive. Granted, Abe seems to be aware of this, but if you think deregulation happens at a snail's pace in the United States and Europe, you're in for a whole new experience in Japan, where policy changes move at glacial speed.

Trade remains very protectionist especially where agricultural products are concerned. No doubt I like my neighborhood markets and local produce a lot when I'm home in Kyoto, but I have been frustrated for 25 years that I can't get the supplies I need to make a decent burrito easily. And finding Thai rice can be a challenge (rice farmers are one of the most powerful lobbies in Japan).

Compounding all this is a near-completely unworkable immigration policy and demographics that are going in the wrong direction as Japanese citizens age and quite literally die off. Without getting too graphic, let me give you an example that will put Japan's demographics into perspective...there are now more adult diapers sold in Japan than infant nappies.

Bet Against Japan's Politicians

Sadly, as much as I love Japan, its people, and its culture, the better bet right now is against its politicians.

1) Short the Yen: We've talked a lot about this over the past year and trades I suggested 16 months ago are now up more than 60%. That, incidentally, is more than double the splash George Soros made last February when the Wall Street Journal reported he'd done the same thing.

If you missed the initial recommendation, don't worry. There's still plenty of runway. After a period of base building in the neighborhood of 100 Yen/$1USD, I expect it to weaken to 150 Yen over the next 24 months. Definitely a slow burner, though, because now that the easy money has been made, the Bank of Japan will do everything it can to "prove" to the world that it's in control just like Bernanke is trying to do in the United States.

2) Short Japanese government bonds: The Bank of Japan dominates Japanese asset markets much more than the Fed does here. That means when the Bank loses control, it's going to be a major liquidity event worldwide. Bill Gross of PIMCO fame alluded to that recently and is of a similar view. My favorite way of doing this is the PowerShares DB Inverse Japanese Government Bond Fund (NSDQ: JGBS) which is designed to exploit the breakdown in Japanese government long bonds as rates rise and the situation deteriorates.

3) Short Japanese equities: The unprecedented Japanese bond volatility that's already played a role in three major global equity shakeouts is just a taste of what's coming. If VaR models get out of line again, the selling will be very fast and very intense. One way to capture that is via the ProShares UltraShort MSCI Japan (Ticker: EWV). Or, simply go short the Nikkei 225 itself. But do it in stages. Better yet, average in by building a position over time.

At the end of the day, nobody likes to bet on economic failure. But it sure can be profitable if you can get over any hang-ups you have about doing so.

Just ask George Soros and Jim Rogers, whose Quantum Fund returned 4,200% over a 10-year period - versus only 47% in the S&P 500 - driven in large part by opportunities nobody else saw at the time.

Related Articles and News:

- Money Morning:

Japan's "Lehman Brothers" Moment: What It Means to You - Money Morning:

Three "Abenomics-Proof" Investments - Money Morning:

Can Kuroda's New Round of "Easy Money" Finally Revive Japan? - Money Morning:

Why Gold Really Crashed and What You Can Do About It

About the Author

Keith is a seasoned market analyst and professional trader with more than 37 years of global experience. He is one of very few experts to correctly see both the dot.bomb crisis and the ongoing financial crisis coming ahead of time - and one of even fewer to help millions of investors around the world successfully navigate them both. Forbes hailed him as a "Market Visionary." He is a regular on FOX Business News and Yahoo! Finance, and his observations have been featured in Bloomberg, The Wall Street Journal, WIRED, and MarketWatch. Keith previously led The Money Map Report, Money Map's flagship newsletter, as Chief Investment Strategist, from 20007 to 2020. Keith holds a BS in management and finance from Skidmore College and an MS in international finance (with a focus on Japanese business science) from Chaminade University. He regularly travels the world in search of investment opportunities others don't yet see or understand.