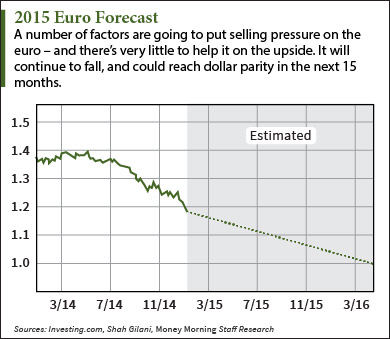

The euro is falling. And our 2015 euro forecast sees little changing over the next year - and for some time after.

The euro is falling. And our 2015 euro forecast sees little changing over the next year - and for some time after.

"The trend of the euro is down," said Money Morning Capital Wave Strategist Shah Gilani. "It would be virtually a miracle for the euro any time in the foreseeable future - meaning the next few quarters, at least, to a year or two - to turn around."

The euro has been sliding for a while, but in just the last couple weeks it crashed through key support levels.

Here's what's behind the euro's recent violent plunge to multiyear lows...

Greece Continues to Drag Down the Euro

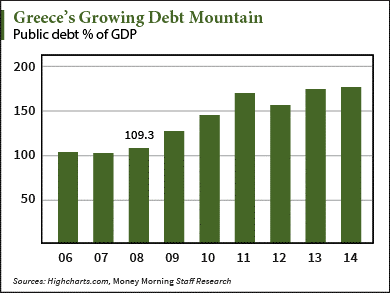

Confidence in the euro is weakening for a number of reasons, but there's one major concern right now: Greece.

Greek elections are slated for Jan. 25. The radical left Syriza party, led by Alexis Tsipras, is leading polls. A Syriza victory will put Greece's future up in the air.

In 2012, Greece was in the midst of a harsh austerity program. Yields rose on Greek debt. It became clear that repayment would be impossible without a bailout. The European Union and the International Monetary Fund offered Greece this bailout - provided they make deep budget cuts.

Balancing the Greek budget proved a difficult task. Unemployment rose. Wages fell. Social programs were cut. And social unrest soon followed.

The Syriza party seized on this climate just before a 2012 summer election.

Syriza emerged as the anti-austerity and anti-bailout party. Their victory would have surely put Greece at a contentious posture toward the stronger Eurozone countries that were extracting austerity conditions in exchange for bailout funds. And that would have increased the chances of Greece exiting the euro, re-adopting the drachma, and devaluing it to stay competitive.

Syriza made gains in the election, but not enough to dethrone the establishment. However, since that election, its influence has grown. Economic conditions are still poor, and the Syriza message is resonating with the electorate.

Syriza is now polling favorably for the upcoming vote. There's a good chance Syriza could emerge the winner. And while Syriza has moderated its stance - Tsipras seems more willing to work with the European Central Bank (ECB) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) than in 2012 - it would still raise a lot of uncertainties.

Syriza is now polling favorably for the upcoming vote. There's a good chance Syriza could emerge the winner. And while Syriza has moderated its stance - Tsipras seems more willing to work with the European Central Bank (ECB) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) than in 2012 - it would still raise a lot of uncertainties.

Tsipras wants to see more debt restructuring. He also wants an end to austerity.

But this is a tall order. Germany ultimately holds veto power over Tsipras' overly ambitious, populist agenda. Any debt restructuring negotiated between the ECB and Greece would weigh heavily on Germany's pocketbook. Germany is, after all, the Eurozone's largest economy.

It's even leaked recently to the press that German Chancellor Angela Merkel is more receptive to a "Grexit." That is, if Syriza wins and demands unworkable concessions.

It's even leaked recently to the press that German Chancellor Angela Merkel is more receptive to a "Grexit." That is, if Syriza wins and demands unworkable concessions.

A Greek exit puts into question the whole Eurozone project. A united European bloc under a single currency, at least in practice, is still a relatively new idea - only 15 years old. And if one of the members leaves, how strong is the project really? And who's next?

That is enough to explain why the euro is falling. The plunge has been entrenched since June 2014, but swung more violently downward coming into the New Year.

But it took a lot of momentum to push the euro to nine-year lows. Even before Greece grabbed headlines again, the euro was crashing.

Here's what is going on beyond Greece that will keep the euro down through 2015...

The Eurozone Is Running Out of Options

When a country is not the sole issuer of its currency, it forfeits a lot of important policy tools when its economy turns sour. This is the nature of the Eurozone. It's why countries like Greece, Spain, and Portugal are in so much trouble.

Take Greece for example. When things got bad, it lost all of its potential growth drivers. Government spending couldn't boost growth because debt loads were already too large and bond yields were soaring.

Consumers weren't spending because jobs were scarce. They also had to deleverage their steep private debt loads. Business investment took a hit as a result of this falling consumption.

Greece could only grow itself through the final component of the GDP equation: net exports. But Greece, not in charge of its own monetary policy, couldn't devalue to make this feasible.

The only option left at that point is a so-called "internal devaluation." Greece would need to tighten its belt. This was the only road to competitiveness.

But as we've seen, austerity has only plunged Greece into social turmoil. Austerity has become a dirty word for the Greeks. And even internal devaluation likely can't make Greece much more competitive, at least not to the level of the Eurozone's stronger players.

"Greece doesn't have the productive means to grow to anywhere near the per capita income of the French or Germans. It has olive oil and tourism, what else?," Money Morning's Gilani said.

Austerity is becoming less palatable to the broader Eurozone. This may very well lead some of the periphery countries to abandon their own internal devaluation measures and look for a European-wide solution.

"The countries have not individually made any of the structural changes necessary, and they're not going to," Gilani said.

That's where the ECB comes in.

"Those countries are going to lean on the ECB to create a Band-Aid... that is going to kill the euro," Gilani said.

Enter quantitative easing.

By buying the sovereign debt of struggling countries, the ECB would pump more euros into the economy. This would devalue it and raise competitiveness.

ECB president Mario Draghi wants Eurozone QE. He has in the past pledged a trillion euros toward the project.

But you might not hear Draghi announce QE in the next ECB meeting on Jan. 22, for one reason: Germany.

Germany is the strongest economy in the region. It's going to have to foot a large part of the QE bill. This is unacceptable for the Germans. They see themselves as a responsible country paying the price for the sins of their less fiscally-restrained neighbors.

Germany also has a painful history of hyperinflation. That alone makes inflationary policy unthinkable.

German officials have even taken the issue of QE to court. They say it violates certain EU treaties.

You see, EU treaties forbid the ECB from financing the debt of any of its member countries' debt. That's not to say those treaties can't be revised, but it does tie up Draghi's hands and limit his arsenal of policy tools in the short-term.

"The Jan. 22 meeting is certainly not a foregone conclusion that the ECB will move to try and get what they have spoken of, which is 1 trillion euro QE ($1.2 trillion)," Gilani said. "You see, the primary goal is they want clearance especially from Germany to go ahead and do the massive QE."

Even so, there's more than enough evidence to suggest that QE is inevitable...

What Yields Can Tell Us About the Potential Eurozone QE

One sign that QE is on the way in 2015 is Draghi has pledged to do "whatever it takes" to save the euro.

But rhetoric aside, bond yields alone suggest something big is coming.

"The ten year yields are so low, they're actually pointing toward depression," Gilani said.

As of Jan. 13, Italian 10-year bond yields are 1.8%. Portugal, a country whose second-biggest lender, Banco Espírito Santo, had to split up this summer over its troubled balance sheet, has seen yields at an undeservedly low 2.6%.

Gilani said that bonds are being bid up by many financial actors.

"The speculators and possibly the banks themselves have front-run what everybody expects, which is a massive QE program," Gilani said. As they bid up the price of bonds, they can turn around and sell them to the ECB to lock in profits. The scope of these purchases are so large that without the ECB stepping in, the Eurozone financial system would be devastated.

"The expectation is that the ECB has to come in and buy them," Gilani said. "If they don't...if [yields] back up a couple hundred basis points, there's going to be massive contagion."

"It's almost as if the ECB has to do something at this point, and the only thing that really could work is the total monetization of European Union countries' debts."

For now, uncertainty in Greece and its potential exit, deflationary concerns, and crashing bond yields are going to continue to fuel lost confidence in the euro.

Believe it or not, shorting the euro isn't the only play on the continent right now... This German automaker has been beaten up, but all that means is you've got a good entry point. Check out this week's "unloved" stock to buy before its share price rebounds...