For most of the Greek debt crisis the reality has been well-known. Even if it was only initially discussed among the staffers and in the back offices of the International Monetary Fund, a Greek default has always been inevitable.

For most of the Greek debt crisis the reality has been well-known. Even if it was only initially discussed among the staffers and in the back offices of the International Monetary Fund, a Greek default has always been inevitable.

So now that Greece is €328 billion ($368.9 billion) in the hole - a 175% debt-to-GDP ratio - exactly why hasn't Greece defaulted on its debt yet?

The Greek debt crisis began in October 2009 when the socialist George Papandreou won a resounding victory in Greek elections and was sworn in as prime minister of Greece. He cracked open Greece's budget books and found that previous administrations had misreported key economic data.

European Union treaties require that member countries limit their yearly deficits to 3% of GDP. Through swap deals with Goldman Sachs that masked Greek debt, and by hiding certain budget items, Greece was admitted into the EU despite what Papandreou discovered to be a hidden deficit that had ballooned to 12.7% of GDP.

The months ahead were marked with credit downgrades and a panic in the Greek bond market. It became clear at that point Greece would be unable to finance its mounting debt by the conventional means of selling bonds on the open market and rolling those debts over. It would need to seek international assistance.

Former European Central Bank President Jean-Claude Trichet and the European Commission attempted to handle the brewing crisis on their own by negotiating a fiscal program for Greece to cut its debt. But they failed to quell panicky market sentiment. So they invited the IMF to help put together a bailout package.

The program was negotiated in May 2010. It involved a three-year disbursement of €110 billion ($123.7 billion) in loans - €80 billion ($90 billion) in bilateral Eurozone loans and €30 billion ($33.7 billion) from the IMF.

Deputy Director of the IMF's European Division from 1999 to 2007, Susan Schadler, wrote in a 2013 report the IMF viewed the proposed program with a lot of skepticism.

She pointed out that a 2010 IMF report hinted at the possibility of a Greek default early on in the process. IMF staffers wrote, "There may be scope to bolster [the bailout package] by seeking coordinated voluntary rollover understandings among creditor groups."

But on the global stage, these discussions of a Greek default didn't happen.

Here's why...

Explaining Why Hasn't Greece Defaulted on Its Debt Yet

The delusions about Greek debt sustainability really began as these bailout packages were being negotiated. It was the head of the IMF at that time, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, who put his rubber stamp on the misguided plan to "save" Greece.

But, as distinguished research professor of economics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, Michael Hudson, told Money Morning, Strauss-Kahn was furthering his own political ambitions, not looking out for Greek solvency.

"Already in 2010 the IMF economists were saying that there's no way Greece could pay," Hudson said. "The IMF economists have been talking to reporters saying, 'We knew they couldn't pay, but Strauss-Kahn, who was head of the IMF at that time, wanted to run for president of France."

"He overruled the directors and the IMF staff and went along with the ECB bailout," Hudson added.

You see, in February 2010, The Guardian reported that France, along with Switzerland, had the most exposure to Greek debt in the world at the time, according to UBS. Strauss-Kahn couldn't risk French banks taking that kind of hit on the campaign trail.

It was all for naught, however, as Strauss-Kahn's political dreams were dashed by sexual assault allegations that surfaced in the year to follow.

But, as current Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis wrote in his 2013 book The Global Minotaur: America, Europe and the Future of the Global Economy, that didn't stop Eurozone officials from "tossing new, expensive loans to an insolvent government that was presiding over an economy in deep recession" in an attempt to "somehow magically render it solvent."

The May 2010 bailout proved insufficient. By July 2011, European leaders had convened a summit to negotiate yet another round of bailout funds for Greece. By October of that year, the new program called for another €130 billion ($146.2 billion) in loans - though the plan wasn't approved until February 2012.

In that interim period, European leaders, having seen the failure of the first bailout package, began to consider a wholesale write-down of Greek debt.

"The European Central Bank was about to take the IMF recommendations to write down the debt very strongly and give a haircut," Hudson said. But that was thwarted in December 2011 by U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, who was taking a tour of Europe to discuss the debt crisis with Eurozone leaders.

"Geithner said, 'no, no, if you do that, Wall Street banks will go under, we can't have them lose anything,'" Hudson said.

You see, Hudson said that at the time, U.S. banks were sitting on a number of credit default swap positions betting that Greece would make good on loans. Any write-down would leave Wall Street on the hook for big payouts on credit insurance written against Greek debt.

Geithner's lobbying for U.S. banks in Europe ultimately won out. He was helped along by U.S. President Barack Obama, Hudson said.

"Obviously Obama threatened: 'Look, if you ever want jobs, we're going to get you fired, we're going to do everything we can to destroy every one of you politically and wipe you out,'" Hudson said. "They're terrified of anything that he'll do."

Times have changed - but the delusions haven't.

It's 2015 and Greece is still struggling to honor the terms of its bailout loans.

The new left-wing Greek government ran on a platform of writing down the debt. With Strauss-Kahn out of the picture, there is no longer an IMF chief trying to mold policy to suit his own political ambitions. The spreads on Greek CDS have widened so much that the trade has been rendered wholly unprofitable. Banks are now reluctant to write up these contracts.

That means the United States no longer feels obligated to lobby for U.S. bank interests in Europe.

So, at this point, the question remains: Why hasn't Greece defaulted on its debt yet?

Greece Is an "Object Lesson" for Spain, Italy, and Portugal

Greece is 2% of the Eurozone. Its default and exit when taken in isolation don't matter.

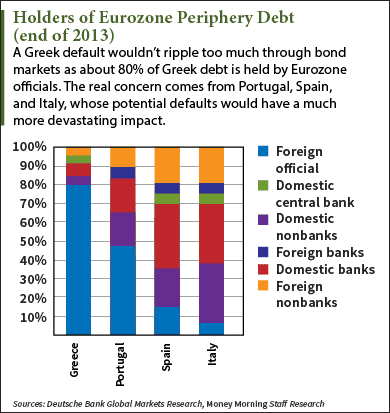

And after two economic adjustment programs, the distribution of sovereign Greek debt ownership has largely moved to official financial institutions and away from private bondholders.

"Almost all of the Greek bonds are held by official agencies," Hudson said. "So it's not going to affect the bond markets. Maybe there will be a few vulture funds that try to sue, but there's hardly any of this Greek debt in the public's hands, it's all in officials' hands. So, none of this will cause more than a ripple."

But Greece isn't the only highly indebted Eurozone country. If Greece defaults, what message does that send to Italy - another debt-ridden country that was close to negotiating its own bailout with Eurozone leaders?

And what about Spain and Portugal? Both countries were actually forced to take bailout money and swallow harsh austerity conditionality along with Greece (and Ireland), though both exited the program with little fuss (as did Ireland).

Portugal, Italy, and Spain represent a much larger pool of troubled sovereign debt that isn't firmly in the hands of officials. That means a Greek default has much broader implications for the Eurozone and the global economy.

If Greece is permitted an easy way out of its debt crisis, these other three countries - and perhaps any future Eurozone member who runs into debt troubles - will be emboldened to default as well.

"All they have to do is say they're not paying the debt. Period," Hudson said. "There's no mechanism for taking them out of the euro legally."

The EC, ECB, and IMF - the troika - have imposed tough austerity conditions and piled more loans on Greece to set an example. Hudson said Greece is "an object lesson." Right now, the troika is merely acting as an arm of the European bank lobby.

"The lobbyists say, on principle, nobody should be able to default," Hudson said. "What they really care about are Spanish debts, Italian debts, and Portuguese debts. And they're saying, 'Don't think you can default because we'll do to you what we're doing to Greece.'"

Jim Bach is an Associate Editor at Money Morning. You can follow him on Twitter @JimBach22.

Exactly how much does Greece owe? We break that down here...