The Eurozone and the Greek people are wondering what happens if Greece exits the euro.

The Eurozone and the Greek people are wondering what happens if Greece exits the euro.

The conventional wisdom is that Greece would abandon the euro, adopt the drachma, and then work to devalue it to boost export competitiveness and grow the economy.

There's one problem. Export-led growth increases the price of imports. It squeezes labor. And for the reform-minded leftist Syriza party determined to leave labor off the table in negotiations - lack of labor reforms from Syriza is the main reason Eurozone officials have refused to release more bailout loans - it wouldn't make much sense for Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras to pursue such a politically suicidal path.

It's also not as simple as adopting a new currency, devaluing it, and then growing.

When the recently fired Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis did a tour for his book, "The Global Minotaur: America, the True Origins of Financial Crisis and the Future of the World Economy," in 2013 - well before he was in the political limelight - he outlined why Greece shouldn't go to the drachma.

A video of his book discussion surfaced earlier this year and was recognized more for one scandalous moment where Varoufakis appeared to "give Germany the finger," but it gave a glimpse into how the Syriza party views a "Grexit."

He didn't buy the argument that Greece could do what Argentina did in 2002, when it defaulted on its International Monetary Fund (IMF) loans.

Argentina didn't abandon its currency and devalue, Varoufakis said. They abandoned a peg to the dollar. The banking system was already awash with Argentinian-issued pesos and the devaluation came naturally.

Greece doesn't have the drachma. It has euros that are rapidly fleeing the country.

"When you don't have a currency, you can't devalue it. All you can do is, you can announce, 'In eight months, we're going to have a currency and, by the way, we're going to devalue it,'" Varoufakis said in that discussion. "Can you imagine a preemptive announcement of devaluation eight months before it happens? This is a recipe for having all wealth liquidated and leave the country."

Argentina also had a ready-made export market, he added. They had tracts of lands with soybeans that China was ready to buy.

Greece has none of that.

The obvious pressures on labor, and the criticisms from a man who was just recently Greece's lead financial representative on the world stage, point to the unwillingness of Syriza to accept a Grexit.

So why did the Greek public, motivated by a new leftist zeal and empowered by their populist government elected in January, vote "no" to more bailout money and raise the specter of a Grexit this past week?

This was a "no" vote that Varoufakis endorsed, by the way.

Here's why...

What Happens If Greece Exits the Euro?

Prime Minister Tsirpas acts on the global stage as though he's ready to negotiate more austerity for Greece in order to release 7.2 billion euros ($7.9 billion) in bailout loans. But in reality, he's come up short on proposing any austerity measures that would squeeze labor further than what past austerity already has.

Greece is buying time. Syriza has accepted that a Grexit may very well be their only option. Tsipras is waiting for a time when that becomes more feasible and doesn't present the type of nightmare scenario Varoufakis conjured up.

While Greece has recently closed down the banks and limited withdrawals to ensure all of the country's euros don't exit the banking system, it hasn't been able to stem what has already been a huge drawdown from its banks.

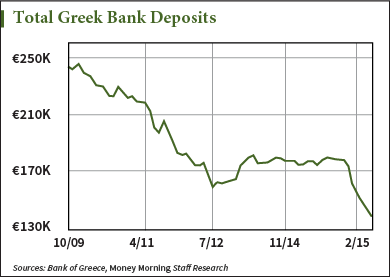

The Greek banking system has been bleeding deposits for nine straight months, according to Bank of Greece figures. From September 2014 to May 2015, deposits have fallen from 178.8 billion euros ($195.7 billion) to 138.6 billion euros ($151.7 billion) - an almost 30% drop.

The Greek banking system has been bleeding deposits for nine straight months, according to Bank of Greece figures. From September 2014 to May 2015, deposits have fallen from 178.8 billion euros ($195.7 billion) to 138.6 billion euros ($151.7 billion) - an almost 30% drop.

The accompanying chart shows how much these deposits have fallen since the Greek debt crisis began in October 2009.

From the beginning of the crisis to the election of Syriza in January, Greek deposits decreased an average of 1.1 billion euros ($1.2 billion) a month. Since January, it has averaged a monthly drop of 6.9 billion euros ($7.6 billion).

Syriza has a vested interested in seeing this accelerated withdrawal, even with new efforts to slow it.

[epom key="ddec3ef33420ef7c9964a4695c349764" redirect="" sourceid="" imported="false"]

It makes a move to the drachma easier. It won't necessarily lead to a labor-crushing devaluation.

"The Greek depositors have been taking their money out of the banks, putting them into euro notes, and the businesses have been taking their money and putting it abroad," Michael Hudson, distinguished research professor of economics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, told Money Morning. "If they go to the drachma, all this foreign exchange is going to come back into the drachma, so the balance of payments will be in surplus. As long as a country has a balance-of-payments surplus, there's no need at all for devaluation."

You see, while pretending to play nice with Eurozone creditors and at the same time refusing to budge on labor reforms, Tsipras has allowed enough time for the Greek public to offshore funds that can later be brought back in should Greece go back to the drachma.

Greece may very well be able to stomach a Grexit.

And that gives Greece a little more leverage, because it undermines the integrity of the euro by reminding other debt-ridden Eurozone members - perhaps Italy, Spain, or Portugal - that there is a better option out there than sticking to monetary union.

The Bottom Line: So, what happens if Greece exits the euro? It could actually lead to an appreciation in the new Greek currency, contrary to the conventional wisdom that it would only lead to devaluation and squeeze labor. This would come as the deposits that have fled in recent months flow back into Greece. And if Greece can exit without sacrificing labor, then it calls into question just how desirable a currency union is if it forces crushing austerity on heavily indebted countries.

Jim Bach is an Associate Editor at Money Morning. You can follow him on Twitter @JimBach22.

Exactly how much does Greece owe? We break that down here...