In military history circles, it's known as "Operation Orchard." A clever journalist once dubbed it "The Silent Strike."

And experts in Middle East diplomacy remember it for an almost total lack of response - a surprising result they characterized as a "synchronized silence."

I'm referring to the Sept. 6, 2007, Israeli air strike on a suspected nuclear reactor in the Deir ez-Zor region of Syria.

The story I'm going to share with you today sounds like a combination spy novel/technothriller, something out of the old Tom Clancy stories.

But it actually happened, and our Members need to know exactly how it happened because, if and when history repeats itself, there will be profound implications - and possibly violent changes - in store for the global economy.

Pull up a chair...

We Find Ourselves Squarely in Israel's Position

Operation Orchard was staged as a preemptive strike on a clandestine facility that Syria apparently intended to use to create weapons-grade plutonium - the key "ingredient" for nukes.

The mission was a complete success: The target was obliterated, and... there was zero fallout - nuclear or geopolitical.

Nearly 10 years later, the still-shadowy story is worth telling again.

Nearly 10 years later, the still-shadowy story is worth telling again.

That's because, like the Israel of a decade ago, the United States of today is being threatened by a rogue nation with nuclear aspirations.

For Israel, that threat was posed by Syria. But for America, that rogue threat comes from North Korea, which on July 4, 2017, test-launched an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) that's believed to have enough muscle to put Alaska and parts of the West Coast in harm's way.

Like the Israel of 2007, the United States of today can no longer ignore the threat - it has to respond.

And like Israel, the United States views a preemptive military strike as one of its options.

But an attack - any kind of attack - carries big risks and opens the door to all sorts of unpredictable outcomes. And, as this story will show, the efforts involved with a strike are massive - much more than most of us imagine.

So there are lessons to be learned from the Operation Orchard saga.

And that means this 10-year-old tale is as timely as ever.

Listen to this story and you'll recognize a lot of parallels between the Syrian situation and the quickly worsening one in North Korea. You'll also see some opportunities the Pentagon missed long ago - and will come away with a pretty good idea of the only cards the Trump administration has to play.

North Korea Has to Be Played "Just Right" to Win... and Survive

[mmpazkzone name="in-story" network="9794" site="307044" id="137008" type="4"]

Like I said, the North Korean nuclear issue is one you need to understand.

Handled badly, this situation could quickly devolve into the kind of crisis that's fully capable of "shocking" the global economy - and global financial markets - into a freefall. Not handled at all, the United States will be staring down the barrel of the worst nuclear threat since the Cold War.

Handled badly, this situation could quickly devolve into the kind of crisis that's fully capable of "shocking" the global economy - and global financial markets - into a freefall. Not handled at all, the United States will be staring down the barrel of the worst nuclear threat since the Cold War.

Handled adroitly, those financial, political, and safety threats will all go away. And certain industries and companies will emerge as clear winners.

Most experts agree that a war with North Korea would start in one of three ways:

- As an escalation following a specific "incident" or misunderstanding

- In response to a rogue strike by North Korea - on South Korea, U.S. allies or military bases (like Guam in the Pacific), or on the mainland United States itself

- Or as a North Korean response to a preemptive strike

And it's that third item - a preemptive strike - that we're going to talk about here today.

Let's start this story with a key fact you need to know about - one that I'm not debating the merits of and that I'm admittedly oversimplifying to help tell this tale.

Israel maintains a stance known as the "Begin Doctrine" - a counter-proliferation policy that includes "preventative strikes" against enemies who are working on weapons of mass destruction, especially nukes.

The policy got its name from then-Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, who in June 1981 authorized an air strike against Iraq's Osirak nuclear reactor in a mission known as "Operation Opera."

There was almost a universal international condemnation of the attack immediately afterward. And experts to this day debate the merit - and success or failure - of the Osirak strike.

But what happened a decade later, after Desert Storm, is very telling indeed.

You see, then-U.S. Defense Secretary Dick Cheney sent the Israeli mission commander a black-and-white photo of the wrecked Osirak facility taken a few days after the raid...

Cheney inscribed it: "For Gen. David Ivri, with thanks and appreciation for the outstanding job he did on the Iraqi nuclear program in 1981 - which made our job much easier in Desert Storm."

Fast-forward to the 2000s. And the Operation Orchard air strike on Syria.

Syria is a signatory to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), meaning it agreed to use nuclear power for peaceful purposes only.

But the country didn't appear to want to keep that promise.

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad took office in July 2000. The next year, Israel's external intelligence service, the Institute for Intelligence and Special Operations - better known as Mossad - started to "profile" the Syrian leader.

Israel started to see evidence that Syria wanted to get its hands on nuclear weapons.

Israel started to see evidence that Syria wanted to get its hands on nuclear weapons.

To be sure, Syria's interest in such heavy weapons goes back a long way. Back in the 1990s, then-President Hafez al-Assad (Bashar's father) had tried to buy research reactors from Russia and Argentina - but was thwarted because of U.S. pressure.

Now, however, the Mossad was hearing that North Korean dignitaries were visiting - and that the visits were focused on deals for advanced arms. No surprise there: North Korea's reputation for selling arms to anyone with cash was well known - one analyst even dubbed the country "Missiles 'R' Us" - a facetious reference to the U.S. toy retailer with a similar name.

Sometime in early 2004, U.S. intelligence intercepted regular communications between Syria and North Korea and traced the calls to a desert spot called al-Kibar, which is 900 yards from the Euphrates River in northeast Syria.

Unit 8200, Israel's codebreakers, put the spot on its watch list.

And the evidence kept mounting...

A Series of "Curious" Events and Violent Accidents

Around that same time - April 2004 - a North Korean freight train headed for the port city of Namp'o suffered a massive explosion. The Ryongchŏn Disaster, as it's now known, remains shrouded in both mystery and controversy.

Shortly after the accident, Pyongyang cut the telephone lines to the outside world and shut off cellular service. One report said the blast was triggered by a cell phone, implying sabotage by a foreign intelligence service.

The Red Cross reported that 1,850 houses and buildings had been destroyed and another 6,350 had been damaged. The death toll may have been as high as 150, with injuries approaching 1,500.

Allegedly among the dead: two dozen nuclear scientists or missile technicians associated with the nuclear-focused Syrian Center for Scientific Research.

According to Gordon Thomas, a British writer who specializes in the intelligence world, the Mossad discovered that those Syrian technicians were riding in a compartment adjoining a sealed railcar. Inside that car: fissionable material that they'd come to collect and take home.

As the story goes, all the technicians were killed... and their bodies flown home in lead-lined coffins.

After the blast, the Mossad tracked a dozen trips by Syrian military officers and scientists to Pyongyang - where they continued meeting with high-ranking North Korean leaders.

All of these things were combining to cause real worry.

Then there was the building.

It was being constructed on that watch list spot at al-Kibar. The facility was big - and enigmatic - says a September 2012 report in The New Yorker magazine.

More insight was needed. The stakes couldn't have been higher at this point.

Classic Fieldcraft Put the Final (Scary) Picture Together

In December 2006, a top Syrian official - the United Kingdom's Daily Telegraph said it was the head of Syria's Atomic Energy Commission, Ibrahim Othman - traveled to London under a false passport. But the subterfuge didn't fool Israel. Agents broke into his hotel room when he was out shopping and installed on his laptop a software program that monitored everything he did on the PC.

The intelligence "haul" from this hotel room gambit was stunning - and sobering. One picture showed Othman together with Chon Chibu, a Pyongyang nuclear official; there were also letters, blueprints, and photographs showing the al-Kibar plant's construction progression.

The intelligence "haul" from this hotel room gambit was stunning - and sobering. One picture showed Othman together with Chon Chibu, a Pyongyang nuclear official; there were also letters, blueprints, and photographs showing the al-Kibar plant's construction progression.

It was discovered that Syria was working with North Korea and Iran, another mortal foe of Israel, on the facility. Indeed, Iran had allegedly funneled $1 billion to Syria to help finance the reactor, reasoning it could also have access to it should its own uranium enrichment initiative fail to reach fruition.

The bottom line: The al-Kibar facility very much resembled North Korea's Yongbyon reactor. And al-Kibar's sole purpose, the Mossad concluded, was to create atomic weapons.

Like we said, Syria is a signatory to the NPT. But it was clear that Syria wasn't sticking with that promise.

In August 2007, Israeli commandos - probably dressed in Syrian uniforms - are alleged to have covertly raided al-Kibar, a move that netted photos, soil samples, and nuclear material, all of which was taken back to Israel.

Analysis allegedly showed that the nuclear material came from Pyongyang.

There are also reports that a North Korean ship destined for Syria was intercepted that summer. Its alleged cargo: nuclear fuel rods for the al-Kibar reactor. Another report states that it docked in the Syrian port of Tartus just days before the raid.

As close allies, Israel and the United States talked about whether the site should be bombed.

Michael Hayden, director of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), was fearful that an attack would lead to all-out war. U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice felt the same way; she allegedly wanted to engage in a six-party talk that would include North Korea and a Middle East conference that would be held here in the United States, The New Yorker later reported.

But other top U.S. security advisors - members of a panel known as the "Drafting Committee" - were skeptical that diplomacy would halt Syria's nuclear program. They believed al-Assad would just stall until the reactor was online (or "hot," in nuclear parlance).

Once that happened, because of its location and the risk of nuclear fallout, a strike wouldn't be possible. (That same worry - that the reactor was going to be fueled - is what ultimately prompted Israel to hit Iraq's Osirak facility in 1981. And it would certainly be an issue with a U.S. strike on Pyongyang's nuclear operations, because there would be radioactive fallout.)

For a Massive Bombing Raid, This Sure Was Quiet

Ultimately, Israel decided to launch a strike on its own.

And it did so on Sept. 6, 2007.

Pay attention to some of the details here: A U.S. strike on North Korea might require some of the same tactics.

A day (or days) beforehand, Israeli commandos were delivered to a spot near the al-Kibar site. Their job when the air raid started: "paint" the target with laser devices that would help "smart bombs" hit home.

A day (or days) beforehand, Israeli commandos were delivered to a spot near the al-Kibar site. Their job when the air raid started: "paint" the target with laser devices that would help "smart bombs" hit home.

Seven Israeli Air Force fighter jets - a mix of U.S.-built F-15s and F-16s - left Israeli airspace and headed for the target. They were accompanied by specialized jets designed to perform jamming, "spoofing," and other electronic missions.

According to reports, the jets knocked out a radar site with precision weapons and jamming. And they "spoofed" the Syrian air defenses with a "false sky" technology that made the air seem free of enemy jets.

Cyber weapons may have been used, too: A May 2008 report in IEEE Spectrum said the Syrian air defenses were effectively turned off by a "kill switch" created and inserted by Israel.

The al-Kibar facility and everything in it was destroyed.

And unlike what happened after the Osirak raid of 1981, the Syrian attack resulted in no backlash, no political fallout.

None at all.

Daniel Makovsky, a writer for The New Yorker, dubbed it the "silent strike."

Egypt's leading weekly newspaper, Al-Ahram, described it as a showing of "synchronized silence in the Arab world." Neither Israel nor Syria ever offered detailed commentaries (Israel's reticence was part of a preplanned tactic designed to minimize backlash in the Arab world.)

Syria went even further.

It immediately started cleaning up the destroyed site - with an efficiency intelligence experts say was more of a cover-up than a clean-up.

Al-Kibar: Like It Was Never Even There

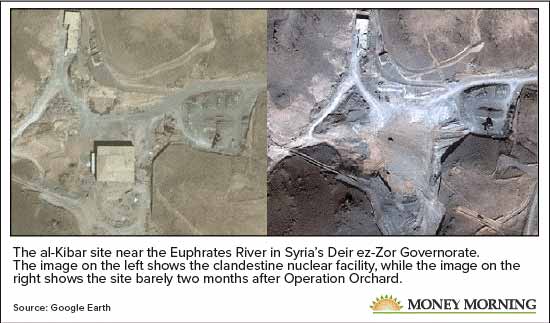

Less than two months after the strike, the site that once housed a building 150 feet on each side had been almost wiped clean, The New York Times said in late October 2007. The before-and-after commercial satellite photos (see them here) are stunning to look at.

That rush to clean the site - something most experts said would normally take years - could be interpreted as an admission of guilt.

"It looks like Syria is trying to hide something and destroy the evidence of some activity," David Albright, a former United Nations weapons inspector, told the newspaper. "But it won't work. Syria has got to answer questions about what it was doing."

Syria had tried so hard to keep its secret that al-Kibar wasn't even rigged with the heavy air-defense systems normally found near such a key facility. And it denied having a military nuclear program, even after the Operation Orchard raid. Indeed, Syria for quite some time was very uncooperative with nuclear inspectors who wanted to assess the site after the raid.

As it turned out, a number of investigations by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) from 2008, 2009, and 2010 finally found evidence of an "undeclared nuclear facility" located there. Samples of processed uranium, graphite, and other "significant" findings made only one conclusion possible.

Finally, in April 2010, IAEA Director General Yukiya Amano said the Syrian facility had in fact been a covert reactor.

Next Friday, I'm going to circle back to this to show you exactly how this affects Washington's available options for dealing with the current North Korean crisis, and I'll give you the tickers of some key U.S. and global companies my research shows will be in a position to help out, and thereby profit, as this either gets resolved, or escalates out of control.

Bill's one of the all-time great stock pickers, and, as you’ve seen, his own research is first-rate. But here's the thing: Bill has totally unrestricted, 24/7 access to every editor at Money Map Press, with all of their best investing and moneymaking ideas. His readers get plenty of those, too. This is powerful stuff – Bill's subscribers just scored their second 1,000% gain - a classic "ten-bagger" - on one of his best recommendations. You can click here to learn how to get Private Briefing yourself.

Follow Bill on Facebook and Twitter.

About the Author

Before he moved into the investment-research business in 2005, William (Bill) Patalon III spent 22 years as an award-winning financial reporter, columnist, and editor. Today he is the Executive Editor and Senior Research Analyst for Money Morning at Money Map Press.