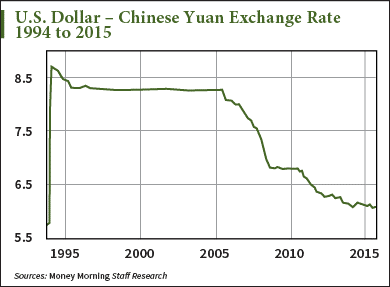

The People’s Bank of China uses its massive reserves to buy or sell the yuan to maintain a desired exchange rate. It’s been pegged to the U.S. dollar in some way for decades.

So, a strong dollar has often meant a strong yuan.

That hurts Chinese exports, and it’s been a sticking point in China’s ongoing negotiations to secure the yuan’s “reserve currency status” at the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

So, when China devalued the yuan by 2% on Aug. 11 – the biggest one-day fall since 1994 – it roiled the global markets.

I wasn’t shocked, though. It was a logical move after all, and its implications open a nice profit opportunity for us...

The Markets Are Asking the Wrong Question

As dramatic as China’s move was, and for all the chaos it unleashed on the global markets, you can see the episode barely registers as a blip on this chart.

As dramatic as China’s move was, and for all the chaos it unleashed on the global markets, you can see the episode barely registers as a blip on this chart.

The question the pundits were asking, or perhaps begging, was, “What was the impetus?”

On the surface, that question is easy enough to answer…

Chinese exports have been slowing, with the July reading down 8.3%.

China’s economy counts on exports for a third of its gross domestic product (GDP). So a move like this was meant to act like a defibrillator, aiming to shock exports back to life.

Another reason is the Chinese stock market. The Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite Index has crashed, now down 42% since mid-June, recording multiple days of 7% or higher losses.

But a cheaper currency and lower interest rates are not the same as structural reforms.

The markets just didn’t get China’s “long game” or the lofty goals China is still working toward.

What China Really Wants

Boasting the world’s No. 2 economy, China wants to join the “good ol’ boys’ club” of truly global currencies. And that means achieving “reserve status” for the yuan with the IMF.

Now, one of the main criticisms of China’s management of the yuan has been its lack of “free market” pricing.

The IMF’s original deadline to decide on including the yuan in its Special Drawing Rights (SDR) currency basket was this fall.

That’s now been officially been delayed by a full year until September 2016, conveniently giving the Chinese yuan time to devalue well before a decision needs to be announced.

Rather than call the Chinese “currency manipulators,” a charge we’ve heard many times from many quarters (especially the United States), the IMF welcomed the move, saying it helped make the yuan more reactive to market drivers.

Effectively, they said Beijing should target a freely floating exchange rate in the next two to three years.

But as always happens with such high-handed interventions, there are going to be some unpleasant unintended consequences.

Waking Up to the Currency War

China’s yuan devaluation ignited fears of a worldwide currency war – and with currency wars, that “fear” often means the war has already started.

You see, despite the PBOC’s reassurance that “looking at the international and domestic economic situation, currently there is no basis for a sustained depreciation trend for the yuan,” the reaction since says otherwise.

The day following the surprise devaluation on Aug. 11, Indonesia’s rupiah and Malaysia’s ringgit hit 17-year lows. Along for the ride, the Australian and New Zealand dollars dropped to six-year lows.

Japan’s finance minister recently warned the weaker yuan could pose risks for his nation. The Nikkei 225 Index has also been hit, given that China is the biggest importer of Japanese goods.

But China’s weaker currency, while making its exports cheaper to others, also makes imports into China more costly.

And no one wants to be left behind…

On Aug. 19, it was Vietnam’s turn, as its central bank devalued the dong by 1% to “keep up” with China and widened the trading band for their currency against the U.S. dollar from 2% to 3%.

The very next day, Kazakhstan’s tenge plunged by over 20% against the U.S. dollar, the result of a government decision to allow it to free float.

The Hidden Risk to the United States

If the situation weren’t tense enough, with the Shanghai Market down yet another 7.63%, China decided to cut interest rates… as if in desperation.

The People’s Bank of China lowered its one-year lending rate by 25 basis points to 4.6%, and the one-year deposit rate will drop 0.25% to 1.75%. Reserve ratios will be lowered by 50 basis points for banks to cover funding gaps.

Then on Aug. 26, the PBOC pumped $22 billion into its economy through the interbank money market in order to boost growth and allay concerns of a hard landing.

I seriously doubt whether any of this will work; a case of perhaps too little, too late.

All of these weakening currencies are causing the benchmark U.S. dollar to get stronger, relatively. In the crucial U.S. dollar/Australian dollar pair, for instance, the Aussie has just hit $0.70.

We know that hurts U.S. exports.

But it also greatly magnifies the risk to the $9 trillion of dollar-denominated debt non-bank borrowers owe outside the United States.

According to the Bank for International Settlements, that’s up by 50% since the financial crisis.

And every tick higher in the U.S. dollar, or every corresponding tick lower in the issuers’ currencies, makes repayment that much more onerous.

That places U.S. Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen between a rock and an even harder place than she’s already put herself in.

The Fed Is Running Out of Options

U.S. multinationals are seeing profits slide as offshore sales are realized in ever weaker currencies.

That heightens prospects Yellen can’t raise rates like she’s been promising for some time.

If the Fed doesn’t raise rates during its next few meetings, the market may interpret this as an unexpected rate cut.

It may even start pricing in expectations of an attempt by the Fed to weaken the dollar in order to help U.S. exporters, U.S. multinationals, and yes, even emerging market debtors.

I’m not the only one who thinks so.

Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, the world’s largest hedge fund, with $170 billion in assets under management (AUM), just told his clients that he thinks the Fed is more likely to head towards QE than to raise rates.

The Fed has already unleashed $4 trillion of QE, followed by Japan’s 125 trillion yen, the UK’s 375 billion pounds, and the Eurozone’s 1 trillion euros. It’s easy to see why the United States might feel pressured to get back into the game, while other emerging markets also fear being left behind.

Currency wars can quickly spiral downward into a vicious black hole.

And that makes precious metals all the more attractive.

The Most Bullish Catalyst of the Year

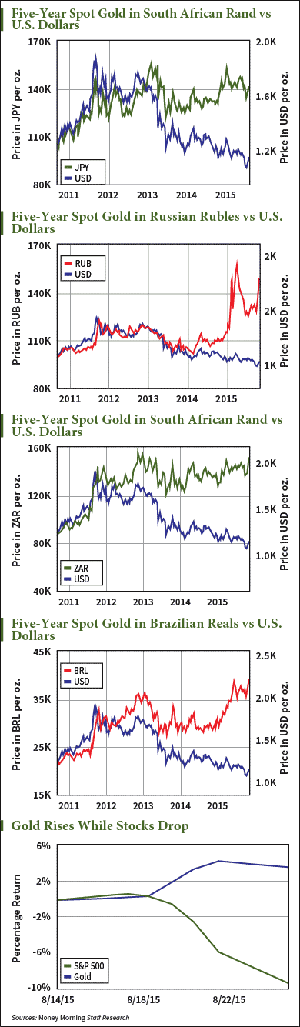

Click to Enlarge

A renewed round of currency wars just might be the “excuse” the precious metals sector needs to finally bottom after four years of correcting.

By the way, gold has actually been in bull mode in a number of major countries, courtesy of their weakening currencies.

Here’s what I mean…

Anyone using one of these currencies has been protected from local inflation by having a reasonable allocation to gold.

Imagine what will happen when markets realize the U.S. dollar is about to be massively diluted by yet more QE.

The dollar will lose its safe-haven status, and people will once again flock to gold.

It may have already begun.

As you can see from the chart at bottom left, last week gold gained 3.8%, while the S&P 500 lost 5.8%.

No one can call the exact bottom in gold or gold stocks except through luck.

That said, it makes for a very compelling buy at these prices.

Gold is financial disaster insurance first and foremost. With central banks desperate to shock their economies back into growth mode, they’re all too quick to devalue their own currencies.

The largest beneficiary of all this will be gold – the only currency that can’t be printed.

Editor’s Note: Money Morning Members can easily get exposure to gold and even other precious metals with an EverBank* non-FDIC insured Metals Select Unallocated Account. You’ll get a $50 bonus deposited directly into your high-yield cash management account when you open a $5,000 account or transfer $5,000 in new money into an existing account. Click here to get started.

*We have a formal marketing relationship with EverBank to bring you benefits like this. Please take a moment to review our disclaimer.