You wouldn't think something with a nickname like "coco bonds" would be so troublesome.

But coco bonds - short for "contingent convertible bonds" - are a major reason for the pummeling that the stocks of several major European banks have taken in 2016. Year-to-date losses range from 20% for Spain's Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria SA (NYSE ADR: BBVA) to 41% for Credit Suisse Group AG (NYSE ADR: CS).

This week, concerns related to coco bonds have chopped 8% from Deutsche Bank AG (NYSE: DB) stock, which is down 35% in 2016.

To understand why this is happening - and why it matters to U.S. investors - we need to know more about what coco bonds are and how they work.

What Are Coco Bonds?

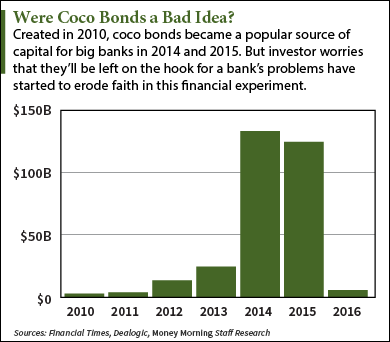

Coco bonds emerged from the 2008 financial crisis as a way to avoid government and taxpayer bailouts of big banks.

As the name implies, coco bonds are bonds - a form of debt sold to raise capital. And like other bonds, cocos pay a coupon to the bondholder. But these bonds are designed for banks and come with a catch.

As the name implies, coco bonds are bonds - a form of debt sold to raise capital. And like other bonds, cocos pay a coupon to the bondholder. But these bonds are designed for banks and come with a catch.

As long as everything is well with the bank, the bondholder collects his payments as with any other bond, although coco bonds pay a premium, up to 6% or 7%. That makes them attractive to yield-hungry investors.

But if the bank's capital ratio falls below a set level, the bank has a couple of options, both designed to preserve capital and make government intervention unnecessary.

In some cases, the coco bond will automatically convert to shares of the bank's stock, hence the name "contingent convertible bond." The bank can also choose to skip coupon payments or even write down the principal.

Obviously, bondholders lose in all cases. Income investors don't want equity in a struggling bank with a sinking stock. A write-down would result in a partial or even total loss of the bondholder's investment. And suspended payments defeat the purpose of holding the bond, making it a non-performing investment.

This is how the European banks have gotten into trouble...

How Coco Bonds Slammed the European Banks

Late last year investors began to realize that the exposure of major banks to such risks as the drop in oil prices (they're the ones making the loans to the oil companies) and the slowdown in the Chinese economy had pushed many of the banks close to the point where they might stop paying their coco coupons.

Deutsche Bank, for example, has had to pay out billions in fines to end several legal disputes and is trying to cope with beefed up regulations that have eaten away at profits. Concerns about capital levels at Deutsche Bank have the holders of the bank's coco bonds worried that it will suspend coupon payments.

Despite assurances from Deutsche Bank's CEO, the bank's coco bonds have become undesirable. Their price has slumped 19% so far this year and is trading at $0.75 on the euro. A similar fate has befallen several other big European banks, with their coco bonds trading at steep discounts.

But while the coco bond issue is centered in Europe - U.S. banks don't use them - it has serious implications for U.S. investors as well...

Why the Coco Bond Crisis Matters to U.S. Investors

Retail investors, even in Europe, typically don't buy coco bonds. But institutional investors both in Europe and the United States, particularly those seeking yield, do buy them. That includes pension and investment funds that you may own.

And most of the European banks in the eye of the coco bond storm have an American Depository Receipt (ADR). That makes them available to U.S. investors and likely to turn up in mutual funds and exchange-traded funds that U.S. investors might buy.

But in addition to possible direct exposure, all investors need to keep an eye on potential problems with the world's major banks, particularly when a large group is involved. As investors learned the hard way in 2008, the world's big banks are central to the global financial system. Trouble there often means trouble for the markets in general.

Coco bonds also present an unusual risk in that it's a new type of investment vehicle untested in the conditions for which it was supposedly designed.

If investors are freaking out just on the hint that the major banks might suspend coupon payments, imagine what would happen in the event of a full-blown financial crisis. The ripple effects would cause stock market crashes the world over.

The coco bond experiment may be failing right before our eyes. Those institutional investors just may decide that the extra yield they get isn't worth the risk of being first in line to bail out the banks when things go south.

The Bottom Line: An investment designed to contain bank "bail-ins" to bond investors is facing its first major test - and it's not doing well. These "coco bonds" are designed to convert to some form of capital in the event a bank's reserves have dropped to a certain level. But coco bond investors in the biggest European banks are getting nervous just at the possibility of suspended coupon payments. And while the problem is focused in Europe, anything that affects major world banks is a threat to all markets - including those in the United States.

Follow me on Twitter @DavidGZeiler or like Money Morning on Facebook.

How Deutsche Bank Will Crash the Markets: Years of shady financial engineering and mounting legal costs have put Deutsche Bank on a path to oblivion. The trouble is, it won't go quietly. Money Morning Global Credit Strategist Michael E. Lewitt says this mismanaged and crumbling institution is a ticking time bomb that could set off the worst credit crisis since 2008. For all the details on why Deutsche Bank poses such a massive systemic risk, and access to Lewitt's free Sure Money service, click here.

About the Author

David Zeiler, Associate Editor for Money Morning at Money Map Press, has been a journalist for more than 35 years, including 18 spent at The Baltimore Sun. He has worked as a writer, editor, and page designer at different times in his career. He's interviewed a number of well-known personalities - ranging from punk rock icon Joey Ramone to Apple Inc. co-founder Steve Wozniak.

Over the course of his journalistic career, Dave has covered many diverse subjects. Since arriving at Money Morning in 2011, he has focused primarily on technology. He's an expert on both Apple and cryptocurrencies. He started writing about Apple for The Sun in the mid-1990s, and had an Apple blog on The Sun's web site from 2007-2009. Dave's been writing about Bitcoin since 2011 - long before most people had even heard of it. He even mined it for a short time.

Dave has a BA in English and Mass Communications from Loyola University Maryland.