By now we all know that Wells Fargo & Co. (NYSE: WFC), one of America's premier banking giants, got slapped with $185 million in fines to settle charges of widespread fraud.

Or was it a screw-up? Maybe management, compliance officers, risk monitors, and auditors simply failed to catch thousands of employees who happened to be engaged in a massive and likely criminal enterprise going back five years.

In fact, this was encouraged by pervasive "trickle-down" bankster culture that puts a premium on profit above, well, everything else. Wells Fargo just managed to get caught at it.

The truth of this isn't pretty...

Wells Fargo Won't Be Popular Much Longer

San Francisco, Calif-based Wells Fargo & Co. calls itself "a diversified, community-based financial services company." Magazines Global Finance and The Banker call it 2016's best U.S. bank. Brand Finance calls it the most valuable bank brand on Earth. CEO John Stumpf was even named 2015's "CEO of the Year" by Morningstar.

San Francisco, Calif-based Wells Fargo & Co. calls itself "a diversified, community-based financial services company." Magazines Global Finance and The Banker call it 2016's best U.S. bank. Brand Finance calls it the most valuable bank brand on Earth. CEO John Stumpf was even named 2015's "CEO of the Year" by Morningstar.

In other words, the Wells' media accolades are plastered on thick and heavy. It's broadly admired (or at least it was), even by an American public who are sick to death of big banks and who, by now, can largely see through them.

Despite the warm, fuzzy feeling Wells seems to give Americans, this is a big bank: Its $1.9 trillion in assets are handled by 269,000 "team members" who deal with 70 million customers out of 8,800 locations.

I've got some more big numbers to talk about...

Wells Fargo has long prided itself in its ability to cross-sell its customers different banking and financial services. Customers with multiple accounts and services are considered "sticky" customers who aren't inclined to leave the bank.

The company reports that its customers use an average of 6.15 services, the highest in the industry.

Cross-selling isn't just a way to keep customers, it's a way to make more money - a lot more - out of each customer. In fact, cross-selling really shines out in Wells' financial and proxy statements.

It shines out so much that cross-selling bonuses and commissions account for between 3% and 15% of sales associates' salaries. The practice is so important to Wells that many employees reported being fearful of losing their jobs should they miss sales goals.

A Los Angeles Times investigation, published in a Dec. 21, 2013, article by E. Scott Reckard, titled "Wells Fargo's Pressure-Cooker Sales Culture Comes at a Cost," lays bare aggressive tactics pushing banker sales teams to cross-sell products like checking and savings accounts, overdraft protection, credit cards, mortgages, and wealth-management products to existing customers.

In the article, Reckard writes, "The relentless pressure to sell has battered employee morale and led to ethical breaches, customer complaints, and labor lawsuits."

Employees reported being forced to work after-hours and weekends to make up missed quotas. The Times reports one branch manager was constantly told she'd "end up working for McDonald's" during hourly browbeatings masquerading as "conference calls."

And now we know that 5,300 "team members," bankers, and branch managers who allegedly set up bogus accounts for customers who never authorized them, to rip customers off and pad their own salaries and bonus payments (and perhaps save their jobs or have a weekend off once in a while), all over the past five years, and all in offices across the country.

Five years. Across the country.

This wasn't someone's fly-by-night quick get-over, get-rich scheme.

Now, three-and-half years after the Los Angeles Times' investigation, we know 2 million unauthorized accounts were opened by employees who simply made up addresses - physical and email - so statements wouldn't go to those customers. They made up telephone numbers, stole customer data, and forged signatures to open new product accounts.

In a statement last week, Oscar Suris, Wells' head of corporate communications, said upon analyzing 93 million accounts it was discovered, though it was unclear, that roughly 2 million accounts may not have been properly authorized. Of those roughly 2 million accounts, 1.5 million were deposit accounts and 565,000 were credit card accounts.

Worse, 115,000 had fees associated with them. I guess management never thought to look a revenue stream in the mouth.

Those in Charge Had to Have Known

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which fined Wells Fargo a CFPB-record $100 million as part of a settlement agreement, says the unauthorized account openings occurred from May 2011 through July 2015.

In addition to the CFPB fine, Wells paid $35 million to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and $50 million in penalties to the Los Angeles city attorney's office to settle their lawsuit against the bank.

Why it took so long for the CFPB and Los Angeles to stop what amounted to identity theft, forgery, and fraud at Wells is another story.

And this had been going on for some time.

According to Wells spokesperson Mary Eshet, the employees in question were "86d" by the bank over the past five years. They've known this was a problem, and that extended much further than just a few rogue operators here and there.

According to Wells spokesperson Mary Eshet, the employees in question were "86d" by the bank over the past five years. They've known this was a problem, and that extended much further than just a few rogue operators here and there.

In fact, Well's chief financial officer, John Shrewsberry, stated last week 10% of the 5,300 fired workers were managers, including branch managers, and that two-thirds of them were located in the southwestern United States.

And so it happens that the business of customer cross-selling becomes the business of selling out customers.

It's the ultimate responsibility of one person, whom Fortune magazine ranked as the 27th most powerful woman in the country in 2015...

Meet Wells Fargo's Sandbagger-in-Chief

Carrie Tolstedt, senior executive vice-president of Wells Fargo's Community Banking Division and chief architect of their "cross-selling initiatives."

When the 55-year-old Tolstedt announced her early retirement this past July, CEO John Stumpf hailed her as "a trusted colleague and dear friend who has been one of our most valuable Wells Fargo leaders, a standard-bearer of our culture, a champion of our customers, and a role model for responsible, principled, and inclusive leadership."

He had a lot more than kind words for Tolstedt...

In a 2015 proxy statement detailing executive pay, the company said it authorized Tolstedt's $7.3 million stock and cash bonus that year (on top of her $1.7 million salary), because "under her leadership, Community Banking achieved a number of strategic objectives, including continued strong cross-sell ratios, record deposit levels, and continued success of mobile banking initiatives."

Tolstedt, who led 102,000 employees in 6,200 retail locations, left with an additional $124.5 million courtesy of stock, options, and restricted Wells Fargo shares, which weren't vested but eligible because she's "retiring."

Despite more powerful "clawback" provisions drawn up in the wake of the 2008-2009 Financial Crisis, which give banks more latitude in "clawing back" bonuses and performance-based compensation from executives who've done wrong, Wells Fargo isn't going after a penny of Tolstedt's bonus package.

She'll likely get to keep all of it in a (very) comfortable retirement.

The facts aside, it looks like high-pressure sales tactics and a win-at-all-costs mentality trickled down from the head of the Community Banking cross-selling throughout the company and bred a culture-within-a-culture.

Or maybe it's just bankster culture rearing its ugly head once again. A different symptom of the same disease that brought us Enron, the subprime mortgage bubble, the financial crisis and all the grief that's come with it.

This Fine, Like the Rest, Is Insulting

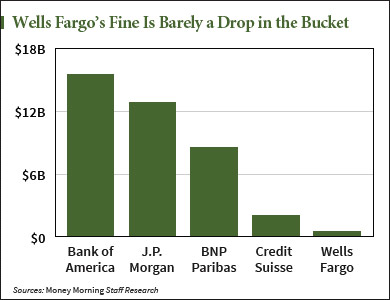

After all, I remember the $1.9 billion slap on the wrist HSBC drew when they settled charges of acting as a bagman for terrorists, dictators, and drug lords. I remember the billion dollars SunTrust paid to settle claims of "legacy" mortgage fraud, and the $13 billion JPMorgan Chase paid for really "legacy" mortgage fraud.

Those fines amounted to a slap on the wrist, a few days' or weeks' worth of revenue. The $185 million Wells will have to cough up comes to even less, of course.

If there's one thing I'm watching for, it will be CEO John Stumpf's appearance before

the Senate Banking Committee tomorrow, where he'll be grilled about the widespread fraud at the bank and its culture.

There'll no doubt be questions about Carrie Tolstedt's pay and what, if any, clawback provisions Wells intends to exercise against her.

Tomorrow's hearing will likely lead to a House hearing and ongoing investigations on the case. The U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of New York and the Northern District of California are the first to conduct investigations, and other district and state and attorneys general are sure to bring follow-on actions.

I'm not expecting much in the way of punishment, but we just might get a pound of flesh out of Stumpf as he's called on to justify or explain these "antics."

I'll let you know what happens every step of the way.

More from Shah: This Is One "Risk" I Absolutely Love to Take

Any time you go against Wall Street, you run the "risk" of upsetting someone. But that's the beauty of this trade. It can bring massive gains every single day the markets are open (M-F) on big-name stocks. Wait till you see how this one turned out...

Follow Shah on Facebook and Twitter.

About the Author

Shah Gilani boasts a financial pedigree unlike any other. He ran his first hedge fund in 1982 from his seat on the floor of the Chicago Board of Options Exchange. When options on the Standard & Poor's 100 began trading on March 11, 1983, Shah worked in "the pit" as a market maker.

The work he did laid the foundation for what would later become the VIX - to this day one of the most widely used indicators worldwide. After leaving Chicago to run the futures and options division of the British banking giant Lloyd's TSB, Shah moved up to Roosevelt & Cross Inc., an old-line New York boutique firm. There he originated and ran a packaged fixed-income trading desk, and established that company's "listed" and OTC trading desks.

Shah founded a second hedge fund in 1999, which he ran until 2003.

Shah's vast network of contacts includes the biggest players on Wall Street and in international finance. These contacts give him the real story - when others only get what the investment banks want them to see.

Today, as editor of Hyperdrive Portfolio, Shah presents his legion of subscribers with massive profit opportunities that result from paradigm shifts in the way we work, play, and live.

Shah is a frequent guest on CNBC, Forbes, and MarketWatch, and you can catch him every week on Fox Business's Varney & Co.