It's only been a little more than a week since Shinzo Abe won election as Japan's latest Prime Minister in a landslide-election victory and the pundits are already lining up telling investors to "buy Japan" because it's "dirt cheap."

The hope is that Abe's promises of fresh stimulus, unlimited spending and placing a priority on domestic infrastructure will be the elixir that restores Japan's global muscle.

As a veteran global trader who actually lives in Japan part time each year, and who has for the last 20+ years, let me make a counterpoint with particular force - don't fall for it.

I've heard this mantra eight times since Japan's market collapsed in 1990 - each time a new stimulus plan was launched - and six times since 2006 as each of the six former "newly elected" Prime Ministers came to power.

The bottom line: The Nikkei is still down 73.89% from its December 29, 1989 peak. That means it's going to have to rebound a staggering 283% just to break even.

Now here's the thing. What's happening in Japan is not "someone else's" problem. Nor is it something you should gloss over.

In fact, the pain Japan continues to suffer should scare the hell out of you.

And here's why ...

The so-called "Lost Decade" that's now more than 20 years long in Japan is a portrait of precisely what's to come for us here in the United States.

Perhaps not for a few years yet, but it will happen just as we have already followed in Japan's footsteps with a "lost decade" of our own.

The parallels are staggering.

Were it not for the names - Abe, Ishihara, Noda - the headlines being played out in Japan could well be our own especially when it comes to campaign promises of unlimited stimulus, more infrastructure development and a busted economy. All three were fundamental pillars in Shinzo Abe's reelection campaign just as they were in President Obama's.

The False Promise of Another Japanese Recovery

So now that Japan has its sixth Prime Minister in six years, will things change? Will Abe's efforts result in a Japanese recovery? Will this be "the" year Japan comes roaring back?

No.

In fact, Japan has just fallen into another recession. The data show that Japan's GDP cratered -3.5% in the most recent quarter. Manufacturing is reeling and several iconic Japanese brands are poised for what will be very expensive and nationally traumatizing bankruptcies.

The country is the most indebted of any nation in the world with the combined total of corporate, private and public debt over 500% of GDP, according to Goldman Sachs.

The demographics are working against the struggling island nation as well. This isn't a policy debate. It's not a partisan issue. It's a numbers game and right now the numbers are getting smaller.

There are a mere 2.8 workers supporting each retiree right now. That's especially problematic at a time when the birth rate is declining so fast it looks like a toboggan run.

Worse, as I noted on Fox Business Network's Varney & Company recently, several surveys show that young Japanese simply aren't interested in sex, so a rebuilding of the domestic workforce is quite literally not going to happen.

You can attribute that to emancipated women, the cost of raising children, work pressures or other economics if you like, but that really doesn't tell the entire story nor get at the root of the problem - a lack of desire.

One survey from O-Net, one of Japan's largest online dating services, interviewed 800 young Japanese men and found that 83.7% didn't have a girlfriend. The survey also showed that 49.3% had never had a girlfriend. Another survey from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare showed that 36.3% of young men had no interest in finding one.

The Wall Street Journal reported that 59% of Japanese females between the ages of 16-19 stated that they are totally uninterested in or completely averse to sex.

Married couples don't appear to be any different. Other data suggest that 40.8% of all couples are not only childless, but sexless as defined by not having had sexual intercourse for more than a month. So called "kamen-fu," or loveless marriages, are far more common than you would think.

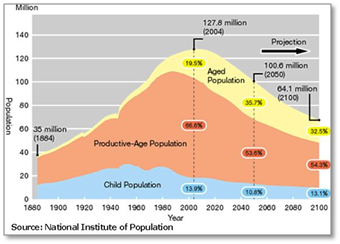

It's no wonder the birth rate has dropped precipitously according to the National Institute of Population. Nor is it difficult to understand that "silvers," which is what the Japanese euphemistically call their senior citizens, will make up 40% of the population by 2060 despite the fact that the total Japanese population is expected to shrink by 1/3rd over the same time frame.

The implications of this demographic shift are tremendous. The newly elected Abe-san can print all the money he wants. He can build more bridges to nowhere and even double the Bank of Japan's inflation target to 2% if he likes.

It won't make any difference on anything other than a short-term basis.

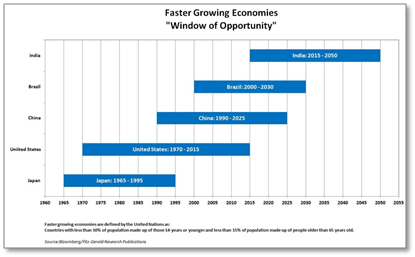

That's because Japan crossed the point of no return and became a "post mature" society in 1995, according to the National Intelligence Council. The term, in case you're not familiar with it, means that there is a disproportionately large number of older people in a given society versus the younger productive and reproductive population.

Put another way, the country's "window of opportunity" quite literally closed.

The Window of Opportunity is Closing Here In America, Too

Many people are surprised to learn that the United States is in the same spot. But they are positively stunned to learn that our window of opportunity closes in 2015 -- only three years from now, when we, too, become a "post mature" country, and the median age climbs above 45 for the first time.

In vehement denial that we're heading down the same path, they explain away the mountains of debt, the failed stimulus, the out-of-control corporations and complete political disarray. But they cannot explain away the demographics here anymore than they can in Japan.

When Japan's markets fell in 1990, the numbers were already going in the wrong direction. The productive-age population had peaked and was in decline. Ours is, too. In fact, so is most of Europe's.

Twenty-two years later it's no surprise that there are fewer jobs and fewer Japanese workers. Nor should it come as a shock that the island nation is reevaluating its immigration policy, its military, and its role in the international community. There are huge, multi-year impacts that are directly related to fertility rates, not the least of which is the inability to kick-start its corporations.

Here in the United States, for example, we tend to think that immigration will be the miraculous do all, end all. Our fiscal survival, in fact, is predicated upon it.

In reality, it makes almost no difference whatsoever.

For instance, the Center for Immigration projects that immigration will increase the working age population to 58% of the total workforce by 2050. That's only 1% above the 57% projected rate with no immigration. If immigration falls, our population curve is indistinguishable from Japan's over the past 50 years.

As for the notion that immigrant children have more children (which is a key assumption in United States population-planning projections) -- that, too, is flawed.

Not only does the data now show immigrant fertility rates are falling, but it also shows that fertility differences between American-born women of child-bearing age and immigrant women of the same age are not enough to increase the share of people falling into the productive working category.

In other words, immigration has only a minimal impact, if any, on slowing down the decrease in working-age population by 2050.

Put another way, there are presently 4.81 workers supporting every retiree over 65 in the United States. By 2050, this figure will shrink to 2.81 workers when you include immigration, and only 2.31 workers without. Remember, Japan's figure is 2.8 today and has dropped since the 1990s.

Many investors gloss over this relationship -- if they are aware of it at all. That's a huge mistake.

By hitching their wagons and their money to populations where the productive population is in decline, investors are dooming themselves to a massive value trap. Sure they can capture periodic market bursts based on stimulus or some other influence, but over time they'll be fighting powerful, self-defeating headwinds because the falling number of people in their productive years ultimately translates into earnings declines and changing purchasing patterns. The opportunity costs are simply daunting.

On the other hand, hitching your wagon to countries with growing productive-age populations, you can capture the "window of opportunity" while it is opening.

That speaks to concentrating your assets and your investments on those choices backed by windows of opportunity still opening --like China's and Brazil's, which do not close until 2025 and 2030 respectively. And India's, which doesn't even open until 2015.

Obviously, all three of the markets I've just mentioned face their own challenges, so let's be clear: I am not saying you have to invest in them directly. Chinese shares are obviously prone to accounting "irregularities." Markets in India suffer from fragmentation. Brazil is struggling with inflation.

But I am saying invest because of them. That means making deliberate decisions to concentrate your assets and your investments in companies that will capitalize on places where the windows of opportunity remain open.

In some cases, that also means investing in those choices where the windows haven't yet opened but are expected to as suggested by population growth.

There's a big and profitable difference for investors who understand the contrast between the two.

Related Articles and News:

- Money Morning:

These Three Iconic Japanese Brand Names Are On My "Short List" - Money Morning:

Is America Having Enough Babies...Or is it Another Sign We're Turning Japanese? - Money Morning:

What Hope Means in Japan These Days - Money Morning:

Godzilla Will Come Out of Tokyo Bay Before Japan Rebounds

[epom]

About the Author

Keith is a seasoned market analyst and professional trader with more than 37 years of global experience. He is one of very few experts to correctly see both the dot.bomb crisis and the ongoing financial crisis coming ahead of time - and one of even fewer to help millions of investors around the world successfully navigate them both. Forbes hailed him as a "Market Visionary." He is a regular on FOX Business News and Yahoo! Finance, and his observations have been featured in Bloomberg, The Wall Street Journal, WIRED, and MarketWatch. Keith previously led The Money Map Report, Money Map's flagship newsletter, as Chief Investment Strategist, from 20007 to 2020. Keith holds a BS in management and finance from Skidmore College and an MS in international finance (with a focus on Japanese business science) from Chaminade University. He regularly travels the world in search of investment opportunities others don't yet see or understand.