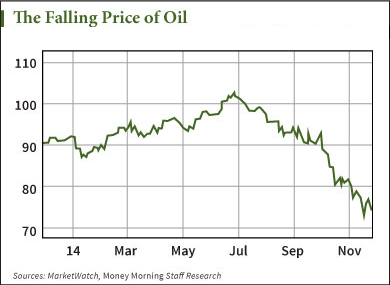

I'd like to fill you in on an interesting wrinkle I've uncovered dealing with the ongoing saga of why oil prices are so low...

Certainly low oil prices have to do with supply and demand. Yet, there's one thing pushing the price down that has nothing to do with the oil itself.

The truth is there has been a concerted shorting strategy underway...

And while the money involved is being sourced from other places like Asia and the United States, this game is being played out through surrogate companies made to sound European, with the trades taking place on European stock exchanges.

A Viable but Dangerous Strategy

A Viable but Dangerous Strategy

Consider the news that hit over the weekend about Tiger Global.

This $15 billion hedge fund has been shorting European stocks through shell companies located in the Cayman Islands. These surrogates have European-sounding names with Gmbh (German), N.V. (Dutch), and other designations to make them sound as if they are based on the continent.

But that is not the case. Tiger Global is a New York City-based entity with the trades coming out of the Caribbean.

Recent revisions in European trading regulations were introduced to make the disclosure of operators like this more transparent. And, at a minimum, what Tiger has been doing is against the spirit of those changes, if not the letter.

Now don't get me wrong. Shorting is a viable strategy during times of high volatility when the dominant trajectory seems to be pointing downward.

Yet, it also is a very dangerous investment approach, because theoretically there is no limit to how much money can be lost.

A short position essentially works this way. An investor who believes a specific stock is going to decline (or continue declining) borrows shares from a broker (usually paying a small premium), and then immediately sells those shares on the open market.

However, the caveat is this. Later the same investor has to then buy those shares back on the open market and return them to the loaning agent.

If the investor is correct and the stock moves down, a profit is earned on the difference in price.

For example, let's say a stock is trading at $10. If I short it and the price goes down to $8, I can then buy it back at the new market price, return the borrowed shares to the broker, and pocket a $2 profit on the spread.

On the other hand, if I'm wrong and the stock increases in value, I have to make up the difference. If the same stock from my example jumped to $20 a share, I would incur a 100% loss in a brief period of time.

The most dangerous approach is to run "naked shorts," a practice discouraged or prohibited on some exchanges. In a naked short, the investor places the trades without actually having control over the shares being shorted. You can lose the farm quickly if the strategy backfires and the stock advances during the period in which the short is held.

Because of this uncertainty, I do not recommend my subscribers short stocks, and certainly would never recommend they use naked shorts.

Nonetheless, times like these have made some companies prime candidates for short activity.

Any stock in question would require enough market capitalization, adequate daily trading volume, and enough accessible shares (a traded company having most of its shares owned by holdings keeping them long-term would provide too much uncertainty).

Oil Prices: Hundreds of Billions in Big Bets

All of which brings me to what I have been talking about in some of my meetings over the past week.

The shorting activity that has been hitting company shares has also been taking place in commodities' future contracts as well - especially in crude oil.

However, in this case, there are two ways to make a short followed by a long trade more powerful. Of course, you need access to a great deal of money, and need to have a trading position to accomplish both of these moves.

In the first case, bets for lower oil prices on futures contracts are made, usually accompanied by "objective" sounding analysis being released claiming the sky is about to fall. Driving the price of the oil down merely allows the practitioner to short into an already falling pricing scenario.

Of course, these shorts, like all the rest, still have to contend with the possibility that the price may suddenly rise for a reason the trader cannot control. When that occurs, one better "cover" a short quickly (by buying it from the market earlier than anticipated), or a substantial loss could follow.

This is the situation in oil today, as traders await a coming OPEC decision.

Short artists are now pressing the price of crude down to maximize their positions, but that could end, causing those positions to be unwound if the cartel decides to cut production in their meetings beginning in Vienna tomorrow.

That introduces the second part of this grand market manipulation.

There is a mantra being conveyed by pundits that the supply/demand balance is holding up because of the new supply coming on line and sluggish demand (which, by the way, has not been the case globally for some time).

But a period of declining prices will always result in a rebound, simply because of the basic principle of petroleum economics. Cheaper prices discourage production but entice end usage.

There's a really attractive way to make money here, but you need to be a very big player to pull it off.

Like a large oil trading company or, better yet, a state-controlled oil producer.

In this case, you would simply yo-yo the availability as the price is going down and move it back when the situation warrants. By withholding supply, a greater profit margin is assured once the price starts moving back up.

After a series of meetings in Paris ending on Tuesday, I can tell you this is what's happening, and I have a good idea which entities are the main players in both ends of this game.

And... surprise! They are rolling out the double squeeze in European trading, using shell companies that are made to sound European in which the money is actually coming from elsewhere. But what is taking place here makes the Tiger Global move against selected companies look like peanuts.

This one has a price tag in the hundreds of billions, once substantial margin buys are factored in. It also has one other huge difference.

The financing is coming from nationally-held and administered sovereign wealth funds, several residing in the countries producing the oil itself.

This is going to make things interesting as I head into meetings in Dubai starting on Saturday...

You can join Oil & Energy Investor for free - go here for more info.

More from Kent: Much was made of the recent U.S.-Chinese accord on climate control, but the excitement surrounding that deal has obscured a very important profit opportunity: Australia. While the United States and China were making strides in climate change initiatives, Australia was inking its own deal with Beijing. In two years, the deal will allow for Australia to pay zero tariffs on several crucial exports. And this little-known Australian oil stock stands to gain...

About the Author

Dr. Kent Moors is an internationally recognized expert in oil and natural gas policy, risk assessment, and emerging market economic development. He serves as an advisor to many U.S. governors and foreign governments. Kent details his latest global travels in his free Oil & Energy Investor e-letter. He makes specific investment recommendations in his newsletter, the Energy Advantage. For more active investors, he issues shorter-term trades in his Energy Inner Circle.