Most of the mainstream financial media is frothing over what Apple Inc. (Nasdaq: AAPL) will do for the Dow.

Apple will join 29 other Dow Jones Industrial Average stocks after the close of trading March 18. It will replace AT&T Inc. (NYSE: T) - a Dow member for nearly 100 years (but for a one-year absence in 2005).

But a look at how Dow stocks do after changes to the index says AT&T stock is headed up...

You see, when you compare the performance of previous Dow Jones rejects with the stocks that replaced them, on average the rejects come out ahead.

Way, way ahead...

The Amazing Success of Dumped Dow Jones Industrial Average Stocks

A 2008 Pomona College study looked at this effect using data from 1928 to the end of 2005.

They found that the Dow Jones rejects collectively gained 175% in the five years after they were removed from the index, while the new members gained just 65%.

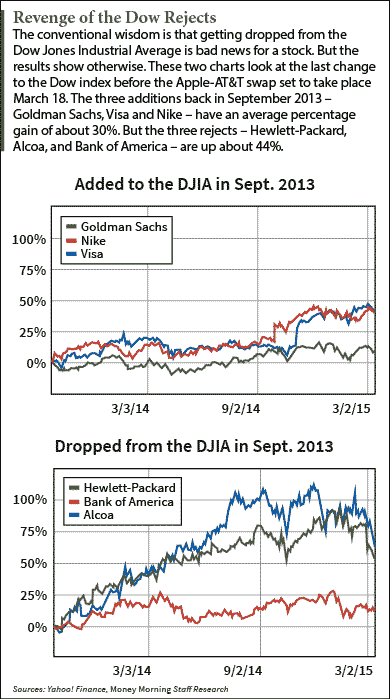

To see this phenomenon in action, just look at the results from the last change to the Dow Jones stocks.

To see this phenomenon in action, just look at the results from the last change to the Dow Jones stocks.

In September of 2013, the Dow Jones added Visa Inc. (NYSE: V), Nike Inc. (NYSE: NKE), and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. (NYSE: GS). To make room for them, the index dropped Alcoa Inc. (NYSE: AA), Hewlett-Packard Co. (NYSE: HPQ), and Bank of America Corp. (NYSE: BAC).

Collectively, the three additions are up 30% since the switch. That's nearly double the gain of the Dow during the same period - not bad. But the three rejects are up about 44%.

That's a 47% difference in profits.

And it's not like this is a statistical fluke. The Pomona study looked at 50 stock substitutions in the Dow Jones over a 78-year period.

What's more, the gap between the two is way too big to be an accident. Investors who buy the Dow rejects when they got kicked out of the index end up five years later with gains 169% higher than investors who buy the newly added names.

To put that in terms of dollars, a $10,000 investment in new DJIA additions would grow to $16,500 in five years. The same amount invested in the Dow rejects would grow to $27,500.

Yet this still leaves the question of why this happens. Such topsy-turvy results seem to contradict all logic.

This makes sense when you look at what's really going on...

With Dow Jones Stocks, the Perception Is Not the Reality

The first error people make when estimating the impact of a stock joining or leaving the Dow Jones Industrial Average is one of perception.

Surely, getting added to the Dow will attract more investors to the stock and drive up the price, right? And getting dropped by the Dow just as surely must mean the stock is a loser to be avoided.

This perception is reinforced by what happens to stocks that move in and out of the Standard & Poor's 500 Index.

Because the S&P 500 is as a threshold for many institutional investors, getting added to the index can mean an influx of new money. And getting dropped means many of these big investors are forced to sell.

But the Dow Jones is a different animal. Any company that gets added is already a thriving, widely held, blue-chip stock. Most investors of all stripes who like it already own it. Joining the Dow attracts little new money. Getting dropped forces no one out.

And that brings us to what's really going on here.

DJIA Stocks Can't Escape This Principle

It's no secret that the Dow Committee - the folks who decide which stocks get included in the DJIA index - like to chase returns. And by the same token, the stocks they dump tend to be the worst performers.

[epom key="ddec3ef33420ef7c9964a4695c349764" redirect="" sourceid="" imported="false"]

But this after-the-fact effort to add winners while paring losers ignores a basic statistical phenomenon: regression to the mean. It simply means that a series of unusually high or low measurements will over time move closer to the average.

"Regression to the mean suggests that companies taken out of the Dow may not be as bad as their current predicament indicates and the companies that replace them may not be as terrific as their current record suggests," the Pomona study says.

This idea is similar to the "Dogs of the Dow" strategy. You just buy the 10 worst Dow Jones Industrial Average stocks and adjust the portfolio annually to keep it in line with the strategy.

In essence, the Dow Committee typically adds stocks when they're peaking, while unloading stocks as they're bottoming out. And as every investor knows, "buy high, sell low" is not a winning strategy.

The weight of the evidence means Dow rejects don't have to be dumped for your portfolio - subject to due diligence, of course.

And it means AT&T deserves a lot more love than it's getting right now.

What Took So Long? Apple has long met the criteria to be one of the Dow Jones Industrial Average stocks. It's the biggest, most influential company in one of the world's top growth sectors, technology. But until recently, it had a problem that prevented it from being added to the DJIA. Here's how Apple became worthy of the Dow...

Related Articles:

- Pomona College: The Real Dogs of the Dow (PDF)

About the Author

David Zeiler, Associate Editor for Money Morning at Money Map Press, has been a journalist for more than 35 years, including 18 spent at The Baltimore Sun. He has worked as a writer, editor, and page designer at different times in his career. He's interviewed a number of well-known personalities - ranging from punk rock icon Joey Ramone to Apple Inc. co-founder Steve Wozniak.

Over the course of his journalistic career, Dave has covered many diverse subjects. Since arriving at Money Morning in 2011, he has focused primarily on technology. He's an expert on both Apple and cryptocurrencies. He started writing about Apple for The Sun in the mid-1990s, and had an Apple blog on The Sun's web site from 2007-2009. Dave's been writing about Bitcoin since 2011 - long before most people had even heard of it. He even mined it for a short time.

Dave has a BA in English and Mass Communications from Loyola University Maryland.